THE UNITING Church has always stood for social justice. It’s in our denominational DNA. In the 1880s and 1890s our former denominations rallied – quite literally – against alcohol and prostitution.

From fighting for Indigenous land rights in the nineteen sixties, seventies and eighties, and upholding Tony Fitzgerald during his investigation into police corruption, to the fight today to keep 17-year-olds out of adult prisons, the Uniting Church has been an ethical watchdog.

Ethicist and retired Uniting Church minister Rev Dr Noel Preston said the Christian faith has always inspired a passion for social justice.

“Christianity is a political faith,” he said. “It is about a way of life; the Christ way, which engages with the powers that be, as Jesus’ way to the cross demonstrates.

“Christian belief must lead to the expression of a practical ethic if it is to have integrity. Central to that ethic will be a primary concern for the most disadvantaged.”

Dr Preston said that while there may be a simple ‘Christian line’ when it came to some public policy, individuals needed to be active in issues of social justice.

“We must engage, act and then reflect and learn for the next engagement,” he said. “The history of the Fitzgerald process and the issues around it, as well as the response or lack of response to it by people of faith, even 20 years on, provides a profound learning experience about Christian witness in society.”

Former Uniting Church Social Justice Advocate (1988-2000) Mark Young agreed that there is still much to learn from the Fitzgerald Report and the years of corruption prior to it.

“The casualties were not only minority groups which dared to disagree, but also the integrity of the judiciary, government and parliament.

“The Fitzgerald Inquiry, and its ensuing reforms, clarified the boundaries between these three vital elements of democracy.

“I believe the churches’ leadership and membership were able to contribute positively to Queensland’s democratic renewal, whether it was done adeptly or otherwise.

“Two decades later it is still important for the institutions and professions of civil society including people of faith, to remain vigilant about the wellbeing of democracy.”

Dr Preston said the Church’s fight against corruption stemmed from Jesus’ teaching to love your neighbour.

“There is every reason for Christians to be guardians against corruption and the abuse of power,” he said.

“If we fail to challenge corruption we fail to love our neighbour.

“Just as the church is in constant need of reformation, so the Christian citizen works with God to constantly renew the world.

“I learnt from Reinhold Niebuhr that the conjunction of self-righteousness, self-delusional innocence and political power is a most dangerous mix.

“I have seen that mix in action in several periods of political history across my lifetime. In a real sense, that was the phenomenon Tony Fitzgerald uncovered in the Bjelke-Petersen years.”

Dr Preston said people needed to be continually aware of potential corruption of power, in the community as well as in the church.

“Religious faith organisations are still learning about what it means to be democratic and transparent, that is, how power can be misused.

“We may be offended to think that corruption lurks behind church pillars, pulpits and curtains, but potentially it does.

“We should not forget that in the lead up to the Fitzgerald catharsis, historically the churches stood by and refused to question how the affairs of state were being run.

“The danger remains today that we are still basically on the sidelines, preoccupied with our own problems rather than engaging with the body politic.

“The call to repentance is at the heart of the Biblical message of the prophets – but only those who are prepared to examine themselves and make the changes we are called to, have the credibility to call others to repentance.

“So we (the church), as well as other parts of society, need to rehear Tony Fitzgerald’s words at the conclusion of his report:

“Vigilance is constantly needed to name the vested interests which will avoid and subvert real reform while creating a new, attractive but hollow facade to hide the continuing misuse of power and misconduct.”

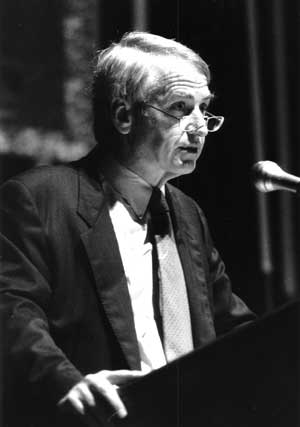

Photo : Tony Fitzgerald QC addresses Christian groups in the late 1980s. Photo courtesy of the Journey archives

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline