Little has changed in the eighty years since Bertrand Russell demonstrated just how adept the church had become at functioning as though Jesus had never existed.

His point is as valid now as it was then.

For instance, consider the fact that few of Jesus’ sayings fit within our truncated, sanitised version of Christianity.

There is something profoundly unsettling still about the unconditionality of his call-to-follow (“Let the dead bury their own dead!”), or his own dark sense of purpose (“Do you think I have come to bring peace to this land? No, I tell you, but rather division!”), or the sheer impossibility of the way of life he envisions (“Love your enemies, do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return”).

Most of us find it hard to imagine the contours of the Christian life or the communal ethics of the church under the condition of such statements.

Everything seems to work much more smoothly when Jesus is treated in abstract – as the path to salvation, as the immediacy of God’s presence, as the symbol of the little bit of the divine in us all.

Historically, it has been the official task of theology to abstract Jesus beyond recognition, while any real engagement with the substance of his message or his concrete practices is left to New Testament scholarship.

But New Testament scholarship so often brings abstractions and palliatives of its own, and any sense of the weight of Jesus’ message is soon lost.

It’s not often that one comes across a serious theological engagement with Jesus’ own moral vision, much less a robust defence of the determinate character of his call-to-follow for the Christian life today.

One remarkable exception to this rule is Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s book Discipleship.

Ten years after Russell’s searing indictment, Bonhoeffer launched an attack of his own on the theological orthodoxy which abandoned Christ and bastardised his message, all the while professing a “pure doctrine of grace”.

For Bonhoeffer, this kind of bland orthodoxy – which he branded “pseudotheology” – was a preposterously complex way of ensuring that we never have to take too seriously the commands of Jesus which gave shape and expression to the Kingdom of God.

“Anywhere else in the world where commands are given, the situation is clear,” Bonhoeffer said.

“A father says to his child: go to bed! The child knows exactly what to do. But a child drilled in pseudotheology would have to argue thus: Father says go to bed. He means you are tired; he does not want me to be tired. But I can also overcome my tiredness by going to play.

“So, although father says to go to bed, what he really means is go play.”

Thus Jesus’ call to radical discipleship is emasculated – stripped of both moral consequence and theological integrity.

All that’s left in its place is the worst kind of idolatry: the invitation to remain secure and unperturbed in the inoffensive embrace of a Messiah of your own making.

However accustomed we’ve become to hearing this sort of drivel from the pulpit, Bonhoeffer was right to denounce it as signifying an abandonment of the way of Jesus Christ that leads inexorably to the cross.

I believe our personal and corporate preparation for this Lent season must begin with the recognition that the greatest threat to the flaccid beliefs and inane practices that have come to define the church is Jesus himself.

Our repentant decision to follow the way that leads to the cross necessitates the abandonment of all those pathetic idols that have become enshrined in our church services as much as they have in our own lives.

If the church is truly to be Jesus Christ existing corporately and visibly in the world, then this is the only Lenten journey that matters.

Scott Stephens is minister at Forest Lake Uniting Church and teaches ethics at Trinity Theological College

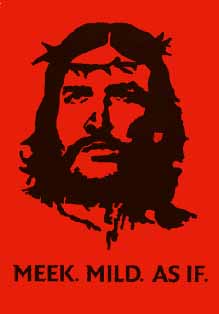

Photo : Image from Churches Advertising Network Easter 1999 www.churchads.org.uk

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline