LAST month, the Kony 2012 film became an internet sensation.

As the film clip went viral, millions of people throughout the world were exposed for the first time to warlord and

internationally wanted criminal Joseph Kony.

Focussing on the plight of children kidnapped to fuel the Lord’s Resistance Army, the groundswell of support for the campaign to bring Kony to justice has been matched by an equally vocal chorus of detractors.

Looking past the hype and hysteria, Crosslight (the magazine of the Synod of Victorian and Tasmania) spoke with Professor Tim McCormack, Professor of Law at the Melbourne Law School and the Special Adviser on International Humanitarian Law to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague.

He appeared for the Prosecution in the presentation of closing submissions in the recent trial of Thomas Lubanga, a

former rebel leader in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Professor Tim McCormack Like so many of my generation, I was introduced to the KONY 2012 YouTube video by my 17-year-old son who insisted that I sit and watch all 27 minutes with him.

We watched it together and again with the rest of the family.

My son knows his old man works for the Prosecutor of the ICC and we’ve had previous conversations about what happens on my regular visits to The Hague.

But the KONY 2012 video was a lightning rod – engendering much more earnest discussion, far more substantive questions and way more focus on what exactly it is that the old man is up to at the Court.

From a purely selfish paternal perspective, I owe the creators of the campaign a deep debt of personal gratitude for the

contribution they have made to my relationship with my teenage son.

All his mates watched the video and engaged in animated conversation about it in person and online.

Epiphanic is how I describe the intergenerational revelation of the power of the medium to effectively communicate a message.

Irrespective of my personal experiences, the timing of the video’s online release could hardly have been more propitious for the ICC.

KONY 2012 was posted just weeks before the Court finally handed down its first ever judgment – convicting the former Congolese warlord Thomas Lubanga of multiple counts of the war crime of child soldiering.

Before the KONY 2012 online video went viral (nearly 80 million hits when I last checked) the acronym ICC was popularly

understood to be referring to the International Cricket Council.

There is a new ICC on the block and it has entered popular consciousness through the efficacy of the KONY 2012 campaign.

But are the campaign’s achievements to date sufficient?

The stated objective of the KONY 2012 campaign is to pressure governments (particularly the US Congress in this Presidential election year) to ensure the warlord is arrested and transferred to The Hague by the end of this calendar year.

What are the prospects?

The ICC has no police force and no powers of arrest.

It is entirely dependent upon the co-operation of governments, peace-keeping forces and multilateral organisations (UN,

EU, AU, NATO for example), to act on court-issued arrest warrants and to transfer accused to The Hague for trial.

Despite recurrent pleadings from the Prosecutor for assistance, Kony and three others LRA deputies have been at large for seven years since the arrest warrants were issued against them in 2005.

Authorities have manifestly failed to take seriously their obligations to assist the Court and I readily join the Prosecutor in hoping that the KONY 2012 campaign has the effect of galvanising public opinion to pressure governments to take more seriously the importance of ensuring that Kony and his cronies face trial.

There are many criticisms of the KONY 2012 video.

Many who watch only it may well assume that Kony is the only warlord wanted for trial by the ICC.

That is, of course, fallacious and a great deal of supplementary popular education has followed in the campaign’s broad wake – assisted in large part by the timing of the ICC’s judgment against Lubanga and focus on other ICC cases.

Some have asked why the focus on Kony rather than on, for example, President Omar Al-Bashir of Sudan?

He is also the subject of an ICC arrest warrant for his alleged genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Darfur Region of his country.

I am untroubled by the selection of Kony as the focus of the campaign.

Invisible Children had to make a choice about which individual and which conflict to highlight and they have been engaged in Northern Uganda for many years.

Why not Kony, particularly given that the campaign has provided a catalyst for much broader coverage of other ICC cases?

There are also facile critiques.

One example is the suggestion that the superfluity of the campaign’s information about the conflict in Northern Uganda

will result in millions mistakenly believing they now understand the Northern Ugandan Conflict.

That sort of reaction to the campaign entirely misses the point.

The overwhelming majority of the 80 million viewers (to date) of the video would simply not engage with a documentary on the history of the Northern Ugandan conflict.

But, those 80 million viewers now know that there is a permanent international criminal court functioning in The Hague,

capable of conducting fair and transparent trial proceedings against those who, in the past, would not have faced trial.

Those 80 million now also know that the Court is frustrated in its work by a lack of determination on the part of authorities around the world to arrest wanted accused.

If just a tiny percentage of those 80 million take the opportunity to launch into a process of selfdiscovery about the peoples

of Northern Uganda – their culture, language, religion and values – the victims of Kony’s atrocities, the campaign will have

made an additional significant contribution.

Other criticisms of the campaign deserve much greater attention and a considered response.

Who are Invisible Children and how do they operate?

What is their commitment to Northern Uganda and what projects do they operate there?

How are those projects received by the local population and what contributions have the projects made?

What percentage of the funds received by the organisation are spent on administrative costs and what percentage of funds raised through the KONY 2012 campaign will be spent on projects in Northern Uganda?

Before I donate money to the campaign I would want to check out the answers to some of these questions.

But the most telling criticisms for me are the ones emanating from the region itself.

The video does not explain that the situation in Northern Uganda is no longer as it was and that the Lord’s Resistance Army has had to move on into other neighbouring countries.

People in Northern Uganda are reportedly trying to rebuild their lives and to move on from Kony’s reign of terror and the

assertion is that many of them are upset that the video does not tell their story or refl ect their perspectives.

There is much talk of justice – for Kony, for the victims, for Uganda, for the international community.

How do we ensure that those who have suffered most are front and centre in any campaign and in any subsequent trial proceedings?

This is a genuinely serious critique and not an easy one to answer.

At the time of printing the KONY 2012 video had had 83,734,012 views on YouTube.

Watch it at http://youtu.be/Y4MnpzG5Sqc or visit Invisible Children’s YouTube channel.

This article is courtesy of Crosslight and appears in this month’s edition.

To read the full article visit www.crosslight.org.au

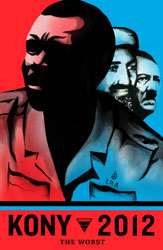

Photo : This poster is part of the KONY 2012 action kit. Image courtesy of www.invisiblechildren.com

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline