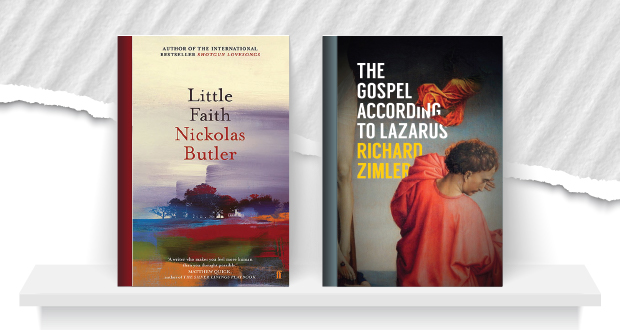

Is faith fervour? Or a holding on in the company of doubt? Two rather different novels explore what it means to live out faith in the world. Nick Mattiske reviews.

Little Faith is set in what has been called “flyover country”, that neglected part of America, midwest small towns where there is a different pace, where there is more contact with the rhythm of the seasons, but where the effects of modernity are more to be seen in decline than progress.

The plot centres on Lyle, a retiree who gains comfort from small town life, despite the decline, who with his wife attends a traditional Lutheran church whose rusting liturgy might be seen as old-fashioned and also in decline. But Lyle finds rhythm and comfort here too, despite questioning the existence of God since the death of his son.

In contrast, his adopted adult daughter is drawn to a charismatic blow-in preacher who has started a Pentecostal, non-denominational church in an old movie theatre. The book shows a careful understanding of the appeal and enthusiasm of such a “modern” church, but it also shows an understanding of how such enthusiasm can hide manipulation and judgment.

The book draws out issues of what it means to love God through loving others, as well as the “elusiveness” of faith, as the pastor of the traditional church—someone whose prodigal son-like worldly roaming in his early days has left him alert to the mystery and not-so-obvious nature of spiritual answers—puts it.

Many American novels focus on the coast-hugging citizens, the glamorous or the outcasts. Here the main character is what is usually thought of as the stalwart, the dependable older person, but a strength of the novel is making this character into a literarily satisfying, psychologically rounded figure, rather than a caricature.

The book also shows how while we have an attraction to certainty, which you might think is a feature of small-town life, such places are more subtle, with people negotiating, especially through churches, a world with a seemingly random mix of good and bad.

The Gospel According to Lazarus takes a different tone. An ageing and exiled Lazarus tells of the disorientation and doubt after his resurrection, his friendship with Jesus, Holy Week and its aftermath. It’s a well-worn story of course, made unfamiliar and immediate not only by the author’s use of names (Jesus is Yeshua and so forth) but also by the depth of evocation of the times and setting. The brutality of Roman occupation contrasts with the life and love-filled Jesus, who is both mystic and revolutionary, a “sandstorm”. Jesus’ knowledge of the Torah is a dreamworld full of resonances and prophecy and direction, and he knows his destiny is to rid the priests of their power because, as Lazarus realises, the priests have made themselves into idols.

Hence the conclusion of Holy Week which is, as Lazarus finds out, for Jesus’ followers not a conclusion. In one way, first-century Palestine is a long way from small-town America, or from Australia, but in another it is not. Jesus’ ministry goes on through his followers, wherever they may be, however they care for others, despite their doubts.

Nick Mattiske

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline