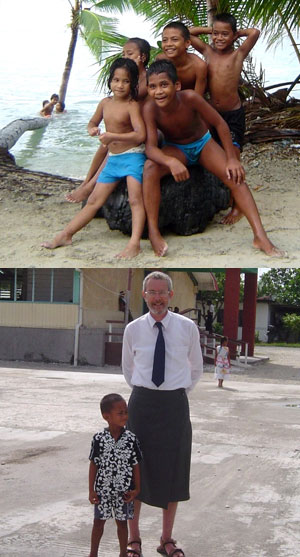

It’s considered good manners in this very polite and very Christian country for a visiting Palagi (Westerner, outsider) to attend Church on Sundays, so I’m standing outside the largest church of Tuvalu’s Te Ekalesia Kelisiano Tuvalu on Funafuti Atoll, the nine island country’s capital, in my sandals, Sulu, white shirt and blue tie, watching locals in their Sunday best, carrying their large and obviously well used Bibles, make their way into the building for service on Sunday February 26 2006.

I only wear a Sulu on formal occasions, such as for this morning’s service, preferring shorts, because I don’t look my best with my skinny, white, hairy, bandy white feller’s legs sticking out beneath the wrap around tailored cloth, but I’m thinking I should reconsider and wear the informal lava lava (wrap around light cotton cloth) more because it’s certainly cooler than my usual shorts.

It’s a typically hot and humid Funafuti morning, the very clement weather occasionally interrupted by showers and storms, always welcome because they top up the island’s water tanks and naturally irrigate the many gardens I’ve seen have sprung up around here since my last visit in late 2004.

If not caught in tanks, including a large concrete tank beneath the open, blazingly white, square between the Church and a Maneapa (open sided meeting house) just to the west, almost on the shore of the twelve kilometre wide and usually placid Te Namo (the lagoon), this tank serving the Church, Maneapa, nearby Funafuti Primary School, and residences, rain water here turns into poison.

A medium-sized horde of Tuvalu’s most precious and beloved asset, its delightful children, have been released from their Sunday School in the Maneapa, three age related groupings having been sitting in circles around their teacher, their respectful heads bowed over their lessons, occasionally repeating the good words to show they’re taking it all in. But even this horde, this Sunday morning, are pretty quiet as they straggle across the hot square, join their elders, and enter the building to await the service.

I asked some Tuvaluan friends what’s the best word to describe a gathering, collection, school, flock, gaggle, horde, whatever, of local children. They laughed and said a komiti might do. The other Palagi words also work well, always said with a warm smile as you watch their antics.

After school on weekdays, Funafuti’s kids fill the streets and villages with their squeals, shouts, and laughter, as they do what kids should always do after school, get out and play. But even then, some children are seated on the veranda of the church or in the neighbouring Maneapa led in Bible study by a Pastor or, if they’re younger, by a matron from the Women’s Komiti – Tuvalu runs on Komitis – somewhat futilely trying to keep the younger one’s attention just a little bit longer.

A curious young fellow comes over to where I’m standing, eyes me off, and, seeing my New Zealand colleague, Jocelyn Carlin’s, about to take a picture of me with the church in the background, politely muscles his way into the shot to stand next to me. We thank him, show him the pic on the digital camera screen, and he heads off to join his family inside the church.

We pay our respects to the Pastor and his wife before the service; we’d met them during previous visits here, and they’re pleased to see us again.

Starting later this Sunday afternoon, Tuvalu will be hit with five days of extreme high tides, peaking late on Tuesday afternoon with the highest tide in almost 30 years. The extreme tides in late January exceeded predictions by several centimetres, and indications are this week’s tides will do the same. Such extreme high tides are nothing new here. They’re part of nature’s cycles, and locals have been coping with them for the 2,000 years people have lived on these tiny atolls and islands.

The highest point of land on Funafuti Atoll is about 3.7 metres above mean high tide. Late Tuesday afternoon’s tide peak is predicted to be 3.26 metres, but staff at the Tuvalu Meteorological Office, located across the airstrip from the tiny international airport with the best destination code in the world – FUN – calculate the predictions will be wrong. They’re also certain their front yard will be flooded, again, to shin and even knee wading depth by sea water seeping rapidly up through the atoll, pushed by the massive pressures of the wide Pacific Ocean to the east, and a rising new moon.

A big myth about Tuvalu, spread by ill informed ‘parachute journalist’s’ reporting, which makes the usually quietly spoken local journos, all friends of mine, really angry, and me as well, is that locals should be huddled in fearful dread, eyeing off nearby coconut palms up which they could scuttle, when an extreme tide looms. Overseas reports suggest Tuvalu’s drowning, sinking beneath the rising sea. True; the sea around Tuvalu has noticeably risen in the 13 years detailed measurements have been taken, about 5 centimetres, but these findings are hedged with caveats, and nobody who knows the solid science on global warming can say with certainty about Tuvalu’s travails, like uncaught rain turning into poison due to sea water seepage into the water table, what’s global warming induced, and what’s amplified by the added stress global warming insidiously imposes on the already fragile Funafuti Atoll environment.

In his Sermon that morning, the good Pastor preaches from Exodus, reminding his attentive flock how, in spite of all, Moses steadfastly believed and trusted in God to see His people to the promised land. Or so said the kind woman seated next to me who whispered the gist of the Tuvaluan sermon into my mono-lingual Palagi ear. I paged through her large, brown leather covered, solidly bound Bible Society published Tuvaluan Study Bible, and smiled at her when she told me how proud they all were at having such new and useful Bibles in their own language. I suppress a snicker when I see a picture of a camel in her Bible, camels not exactly a common sight on Funafuti Atoll, Tuvalu. Many extended family households keep a few pigs penned in their yards or nearby, fed on kitchen wastes and coconuts, which are killed, and cooked in umos, or earth ovens, for feasts, family occasions such as weddings or birthdays, or as contributions to lively Tuvaluan celebrations called Fatele, which are always great fun to attend.

In the announcements, the Pastor reminds folk that there are extreme tides looming, to take precautions, that the Church, the Red Cross, and the government’s disaster komiti are ready to respond to any emergency, and to trust in God to protect them.

Many, especially older, Tuvaluans explicitly believe God’s promise to Noah, and to humanity, to never again flood the earth (Genesis 9: 1 – 17). The glorious rainbows, arching across the horizon, over Te Namo to the west when the conditions are right are a breathtaking reminder of that Holy Covenant. For these Tuvaluans, all this talk of global warming, seas rising, and Tuvalu drowning is just Palagi stuff. But the elders also tell how the climate’s changed, the storms are more and worse, the drought’s longer, the reefs are crumbling, fish catches lower, and breadfruit, pandanus, and coconut harvests not as bountiful.

They can’t even grow their equivalent of potatoes, a large, slow growing tuber called Pulaka, because the deep mulched pits in which they carefully tend the plant, using secrets passed from father to son, are polluted with seeping sea water, the yellow edges on the plant’s elephantine dark green leaves a sure sign the tuber is rotting in its pit. You see their worry and frustration etched into the old fellow’s brown wizened faces as part of their food supply and their traditions are dying.

To be sure, Tuvaluans, like the rest of us, urgently need to relearn and apply Biblical principles of good stewardship, informed by modern environmental science, because one of their self-inflicted environmental stresses is pollution caused by a serious solid waste disposal problem on the 12 kilometre long boomerang shaped capital atoll, with unsightly and unhealthy dumps fouling the ends of the road which runs the length of the atoll, and several water filled ponds, called taisala, left over from World War Two excavations.

I don’t think it’s accidental that the author of Matthew’s Gospel has Jesus teaching about the good steward (Matthew 25: 14 – 30) to make the point that good stewardship involves responsibly using God’s gifts with care. The theological term for our bad stewardship of God’s good earth, and sea, and air, is sin.

Given their tiny economy, $US 11 million GDP, and equally tiny population of 11,500 across the nine small islands in a 900,000 square kilometre exclusive economic zone, with 4,500 squeezed on to the 2.79 square kilometres of land on Funafuti, Tuvaluans do need sensitive and appropriate assistance to respond to their challenges, which they’re getting up to a point, and they are seriously grappling with those challenges themselves. The national slogan, Tuvalu mo Te Atua (Tuvalu for the Almighty) works as an entry point into discussions, plans, and escalating effort to respond to natural, and human-caused environmental assaults.

Global warming and sea level rise just further amplifies those challenges, but Tuvaluans themselves are not causing these added assaults to their very existence as a people.

In Tuvaluan, the saying Tatou ne Tuvalu Katoa is invoked to remind people that ‘We are all Tuvaluans’ so let’s keep working together for the benefit of all Tuvaluans. Though Tuvaluans are a very self-effacing, humble people – their apologising can drive me nuts at times! – many allow that ‘We are all Tuvaluans’ can also mean, given the grave threat global warming poses to the entire planet, We, everybody, is, in an important sense, a Tuvaluan, each threatened, and challenged to properly respond. Tuvalu’s just more gravely and immediately threatened because it’s so small and remote.

Sitting in church that Sunday morning on Funafuti Atoll, my attention to the service wandering because it was all in Tuvaluan, though I could follow its stages and the hymns because it’s Order of Service is similar to the Uniting Church’s Order of Service, and my friend next to me was whispering an English summary of what was going on, I was once again meditating on a passage in Matthew that haunts me whenever I think about Tuvalu, its kind and gentle people, my dear friends there, and especially the laughing, noisy, playing children whose deep brown eyes you look into at your peril because they’ll steal your heart, and dazzle you with their smiles as they do so.

No Tuvaluan would dare presume this, but I’ve talked about it with their Pastors, and they’re comfortable about how I work it through.

After Jesus’ teaching about stewardship in Matthew 25: 14 – 30, the very next passage is the ‘Judging the Nations’ discourse, Matthew 25: 31 – 46.

As I sat at the back of the church that Sunday morning, I, an Australian ashamed to be so because of my government’s mean and hard hearted stances on Pacific labour migration, tied overseas aid where most of it ends up back home, and Regional responses to global warming and sea level rise with the attendant probability of environment refugees seeing succour here when their beloved homes become uninhabitable (though nobody can precisely predict when this might be, data pointing to this dire future for Tuvalu is steadily firming up), surrounded by devout Tuvaluans in their Sunday best, felt closer to Jesus than I’ve felt in a long, long time.

When their Pastors preach upon that terrible, awesome passage, Matthew 25: 31 – 46, Tuvaluans can clearly see that Jesus is standing in their midst.

While not entirely disbelieving in the power of prayer, I also take good science seriously, so later that Sunday, I braved the ferocious mid-afternoon heat and blindingly dazzling reflected light from the concrete to walk across the air strip to the blessedly air conditioned Met Office to check the all but finalised three day weather forecast.

A convergence zone high in the atmosphere above the group would cause the weather into the extreme high tide week to be calm, hot, and pretty still, with only 5 – 15 knot north to north westerly winds and occasional passing showers. Glorious picture postcard tropical atoll weather colleagues back home in Australia would deeply envy me for experiencing.

And so it was when, at 5.30pm on Tuesday, February 28, Funafuti Atoll had a record high tide of 3.48 metres which only caused localised sea water seepage flooding at several parts of the atoll, and only a few houses had to be temporarily evacuated.

We were very, very lucky the weather was so benign.

Or the prayers we prayed on Sunday actually worked.

Dr Mark Hayes is a Brisbane-based writer and academic who teaches part-time in the journalism course at the University of Queensland. A much longer article, researched and written during his third visit to Tuvalu in February and March, 2006, will be published in the May 2006 edition of Griffith Review, together with exclusive pictures by New Zealand photographer, Jocelyn Carlin, with whom Mark collaborated while on Funafuti Atoll, Tuvalu.

His latest visit to Tuvalu was assisted by a modest grant from the Uniting International Mission National Agency of the Uniting Church in Australia.

More information about Tuvalu, including many unique and exclusive pictures, can be found at the Tuvaluislands.com Web Site: http://www.tuvaluislands.com

Photo : Top: Tulaluan children preparing to steal another Palagi’s heart. Photo by Dr Mark Hayes. Bottom: Dr Mark Hayes wears a Sulu to church.

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline