For every death by suicide, Lifeline estimates that every day as many as 30 people make an attempt, and 250 make suicide plans. Ashley Thompson speaks with Christians affected by, and called to care for, those living with suicidal thoughts.

Trigger warning: What follows is a retelling of people affected by suicide and/or involved in crisis support. If you should ever need to talk to someone about your own or another’s mental health, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. If a life is in danger, call the emergency services on 000.

“He was much more than how he died,” says Newlife Uniting Church member and trained counsellor, Liz Adams.

“It is important that his death doesn’t become our memory of who he was.”

In your darkest hour

It was a chaotic morning in 2001. One child was late for the bus and another had an assignment due—but the printer was playing up and Liz had somewhere to be.

Amidst the usual morning rush, Liz’s youngest son (ten) answered a knock on the door as she attempted to sort out her daughter’s (13) botched printout.

“I said ‘just tell them to wait for a few minutes’!” recalls Liz, “but then he came back and he said ‘no mummy, the police’.”

Frazzled, Liz ignored her son and continued helping her daughter.

“The next minute they [the police] are standing in front of me asking me where our son was, our oldest son,” says Liz.

Confused, Liz explained he was out with his father training in the surf—she didn’t take him this morning, so he must have.

“Then they said ‘There’s been a body found … and it had your son’s identification’.”

Confused and agitated Liz laughed it off as a prank by his mates, “They’re always taking each other’s clothes.”

“Then he said, ‘Does your son ride a triathlete bike?’ … and it all clicked.”

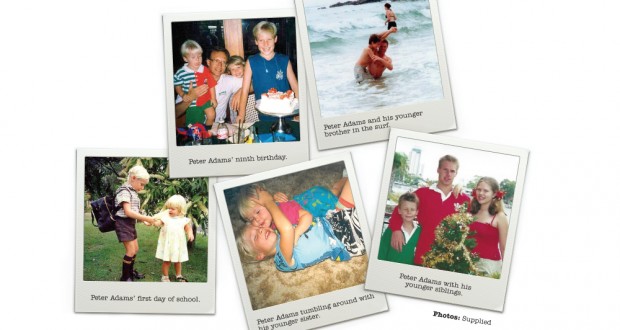

Liz describes the feeling of finding out her 16-year-old son Peter had ended his life like “an incredibly hard punch in the heart.”

“It takes your breath away and you can’t breathe and everything stops.

“You become numb.”

Left behind

Fourteen years later Liz is a counsellor at Newlife Care, training to be a clinical psychologist and studying the outcomes of suicide bereavement on children who in her words are “taught to suppress their feelings so they don’t distress their parents”.

Liz believes it is vitally important we break the silence around suicide because, “Whatever we’re doing at the moment is not working”.

“More people die by suicide than deaths on the road and murder combined in a year but no one’s doing anything.

“How many people drown and we have life savers, we train our children, we do all kinds of things to protect people on the beach but seven people every day die by suicide and what is the community doing? We pretend it doesn’t happen.”

How to help

According to Liz, the theory of suicide tells us there are three components that at intersection have a deadly mix. These are: a sense of not belonging, a sense of being a burden and other volitational factors including fearlessness and high tolerance to pain.

“We can’t help people with fearlessness and we can’t help people with a high tolerance to pain but the church can help people feel like they belong, to each other and to a place. We can also make people feel like they’re not a burden,” she says.

Rev Dr Paul Walton is minister with Centenary Uniting Church. He is open about living with depression.

Paul stresses that, “Mental illness is not a sin, nor a sign of a lack of faith.

“It is simply not true that if only people had more faith they would not be ill. When I was at my most depressed, it required faith just to get through the day,” says Paul.

He believes the church can help by encouraging faith, preaching forgiveness and not demanding more.

“When I was at my most depressed, I told the elders in my congregation about it and their immediate response was, ‘What can we take from your workload so we can help you?’

“They willingly took on a couple of things that were weighing me down. This support was invaluable.”

The Queensland Synod’s newly available publication Called to Care offers a suite of free mental health resources for congregations who wish to support those suffering with mental illness.

Penning the theological introduction to these resources, Rev Dr Paul Walton encourages Christians to respond from a place of generosity, not fear; we are all broken people. He champions the local congregation as a safe and welcoming place for the healing of wounded people.

Living on suicide watch

Lifeline Telephone Crisis Support operator, Dorothy Walsh has also suffered from depression and experienced suicidal thoughts. She would have given anything for someone to only ask, “Are you OK?”

“That’s all I wanted. I wanted—almost like a sign on me to say—somebody notice me!” says Dorothy.

“It wasn’t until somebody said to me, there’s a particular female doctor we think you should go and see, and I sat down in her chair and just cried and cried and she asked, ‘Are you thinking of taking your life?’ and I said, ‘Yes’.

“‘I want to put my kids in a car and drive off a bridge’.”

Dorothy was more than relieved to have these thoughts finally in the open, “Because it was a way forward”.

When asked whether the impact she would leave on her family had any influence in stopping her actions she replied, “No, no, not at all. It was about making it stop.”

At the time it seemed to Dorothy that her death would have been an “absolute service, because I wouldn’t be a drain on anybody anymore. And that was really strong, those thoughts.”

She later realised the irrationality of her thinking and that at times all a person needs is to have someone “interrupt your thoughts” because, “You have really wrong thinking when you’re depressed”.

Paul Walton echoes these feelings as typical of someone suffering from severe mental illness.

“It is a terrible thing, but when a mentally-ill person commits suicide they are showing that they have found life to be unbearable.”

Called to care

Finding a way forward in this emotional, spiritual and psychological world of pain can only be achieved through forgiveness, says Liz.

“My husband and I, we had to forgive him [Peter], we had to forgive ourselves, we had to forgive others—there were other people we were very angry with.

“We have a God that is a God of the second chance. We have a God that can redeem the worst situation and bring good out of evil and that was very clear to us.”

Liz remembers Peter as a “whole” person: “terror”, “larrikin”, warts and all—anything less would deny him his humanity.

“He lived for 16 years and he was an amazing, wonderful, frustrating person.

“How he died was not who he is.”

If you ever need to talk to someone about your own or another’s mental health, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. If a life is in danger, call the emergency services on 000.

Access the Queensland Synod’s newly available, free mental health resources at ucaqld.com.au/calledtocare

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline