IN HIS infamous essay Why I am Not a Christian, Bertrand Russell remarked that the word Christian “does not have quite such a full-blooded meaning now as it had in the times of St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas.

“In those days, if a man [sic] said that he was a Christian it was known what he meant… Nowadays it is not quite that,” he said.

This comment reflects the state of atrophy in which Christianity now finds itself: a steady process of being alienated from its own essence and growing increasingly vague and indistinct.

Yet it is one of the strangest aspects of our time that shards of a lost authenticity can be found in some of the most anti-Christian of sources.

The offensive strangeness that the Christian message historically embodied is frequently more discernable in sources other than the impotent expressions of official Christianity.

Karl Marx said it best. “Shame on you, Christians, both high and lowly, learned and unlearned, shame on you that an anti-Christian had to show you the essence of Christianity in its true and unveiled form!”

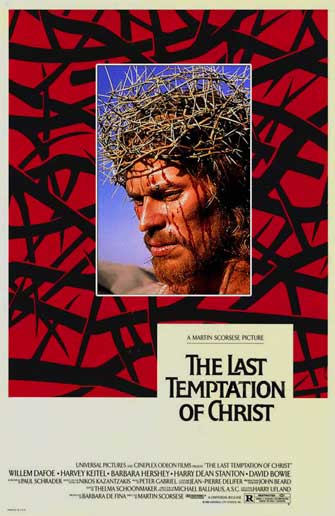

So perhaps one of the paradoxical tasks given to us is to encounter the truth in the likes of Andres Serrano’s photograph of a plastic crucifix immersed in his own blood and urine; or buried deep in the pages of Darwin’s scientific notebooks; or even amid the moving images of Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ.

Scorsese received one of his six Oscar nominations for best director for this 1988 film, not least for his sheer chutzpah and long-term commitment to this project in the face of intense opposition, but, as on every other occasion until recently, he missed out.

Drawing inspiration from Nikos Kazantzakis, The Last Temptation of Christ presented a radically different version of the Jesus story than other more sanitised depictions.

Played by Willem Dafoe, Scorsese’s Jesus, like all his protagonists, is a tortured soul haunted by a divine vocation that brings with it not enlightenment, but darkness, confusion and oppression.

Jesus’ experience of God as an expansive, entirely free presence can no more be apprehended by the young Galilean’s marginalised psyche than it can by the temple in Jerusalem.

Thus, the psycho-spiritual journey of the film is not toward some deep sense of Jesus’ ‘secret identity’ and a clearer realisation of who he is and what he must do, but rather away from any such security.

He is plunged into the divine void and needs only to be willing to resign himself to it to find salvation and sanity.

This is where the film’s near fatal weakness lies. It reduces Jesus’ message to an anti-establishment spiritualism or even vulgar pantheism, over and against the rigid formality of Jewish ritual.

As Scorsese’s Jesus puts it at one point in the film, “God is an immortal spirit who belongs to everybody; to the whole world.”

By casting God as an all-embracing life spirit rather than some tribal deity, the film locates the critical opposition as being between Jesus’ free spirituality and Judaism’s stale religion.

The Last Temptation of Christ is undeniably wrong here. In the Gospels, Jesus sets the conflict within Judaism itself, between the holiness code and prophetic traditions.

But the film in equal measure gets something remarkably right. A strong temptation did bedevil Jesus his entire life. It was a temptation as much domestic and familial as it was national and political.

And while this temptation wasn’t purely internal (an ‘illness of the soul’, as the Puritans used to put it), neither was it entirely external. It went to the heart of Jesus’ self-understanding.

Take Luke’s account of Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness. What is missed in our usual readings of this account is that the expectations and birthright of the messiah – condensed into allusions to Psalms 2 and 91 – are presented as temptations, and from the devil’s own mouth, no less!

The effect of this outrageous assertion is that one is forced to reinterpret Mary’s and Zechariah’s hallowed songs, both of which eagerly anticipate the coming deliverance of Israel from its Roman oppressors, as almost ‘satanic utterances’.

Jesus’ refusal to submit to this temptation was an absolute rejection of the notion of ‘messiah’, and thus of his family, his nation, and ultimately of that God known as ‘Yahweh’.

This implication was perfectly captured by Scorsese’s Jesus when he cries, “God is not an Israelite!”

The prophetic path on which he then embarked was one of urgent warning: that the nationalised structures of holiness and insurgence will not lead to deliverance but to the destruction of Jerusalem itself.

It was this protest – which entailed an altogether different conception of God, one that is defined by mercy but whose dark purposes include Jesus’ own death – that was burned indelibly into Jesus’ self-understanding.

His crucifixion – a form of execution reserved exclusively for insurgents and rebels against the Roman occupation – was the final warning that further revolt would end in national catastrophe. Or, in Jesus’ own words, “If they do this when the wood is green, what will happen when it is dry?”

At this point, Scorsese is unique among cinematic depictions of Jesus’s life. He accurately connects the necessity of Jesus’ crucifixion with the impending destruction of Jerusalem.

If the ‘last temptation’ of Jesus was to succumb to the weight of national and familial expectations and thus pull back from the darkness and uncertainty of his vocation, perhaps our temptation this Easter season is to give in to the security of those all-too-familiar portrayals of Jesus, and thus miss the power of his resurrection.

Scott Stephens an author, theologian and minister at Chermside Kedron Uniting Church is a regular contributor to Journey.

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline