IN HIS review of Don DeLillo’s highly acclaimed novel, Under-world, James Wood observed that “the book is so large, so ambitious, that it produces its own antibodies and makes criticism a small germ”.

That same description could apply just as easily to capitalism. Every attempt to curb its voracious appetite, to ‘humanize’ its world-wide dominion, to place the economy back in the service of the greater good and thus temper its lust for unregulated growth, has not simply failed, but has been assimilated, folded back into the existing economic order and turned into yet another expression of capitalism itself.

Take, for example, the wide-spread use of ‘anti-globalization’ rhetoric by designer labels and marketing firms, or even the current wave of chic enviro-funda-mentalism.

In both cases, there is a kind of coming together of opposites, where two trends which are logically opposed (like popular consumerism and radical conservationism) come to occupy the same space, and seemingly without contradiction.

So, the exemplary products of global capitalism are T-shirts made in Chinese sweatshops bearing the “World Without Strangers” motto.

An astounding instance of this absorption of a potential criticism of capitalism into the inert safety of pop culture can be found in the book version of Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth. Its back cover features an endorsement, not from Sir Nicholas Stern, nor even from Tim Flannery, but from none other than Leonardo Di Caprio!

I suppose there is a connection between Leo and big chunks of floating ice – but wasn’t his problem that the ice hadn’t melted?

Yes – capitalism, too, produces its own antibodies. And nothing is outside its grasp.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of global capitalism is to have made choice one of those inalienable human rights, to have ensnared the very notion of democracy within an indiscriminate right-to-excess.

This is an achievement that DeLillo grasped in a remarkable way. As he put it in Underworld:

“Capital burns off the nuance in a culture. Foreign investment, global markets, corporate acquisitions, the flow of information through transnational media, the attenuating influence of money that’s electronic and sex that’s cyberspaced, the convergence of consumer desire – not that people want the same things, necessarily, but that they want the same range of choices.”

Choice itself has thus become the true object of human longing, a longing that goes right down to our genes. The latest of Michael Bay’s awful films, The Island, expresses this point particularly clearly. Lincoln Six Echo (Ewan McGregor) and Jordan Two Delta (Scarlett Johansen) are two survivors of an alleged nuclear holocaust, who now live, along with hundreds of others, in a sterile, asexual, infinitely regulated environment – part fitness-centre, part preschool, part prison.

But a deep desire grows within these innocents, a spontaneous genetic mutation that craves the corrupting excesses of life (in the form of five strips of bacon at the beginning of the film, and the “lots and lots of sex” that causes Lincoln’s liver failure at the end), leading them to break out of their prison and find their own ‘garden of earthly delights’ on the streets of Los Angeles. The terrifying, but all too actual vision we get in The Island is of capitalism that has gotten into our genes and colonised human nature itself.

Karl Marx was right: the vision of capitalism that embraces the entire globe, that can generate more money ex nihilo through the mysteries of financial derivatives and futures speculation, that can bring together polar opposites in apparent economic harmony – is, in the end, theological. Or, to put it another way, capitalism is Mammon.

So the question is, how can we take Jesus’ statement – “You cannot serve God and Mammon” – seriously when God and Mammon are now in cahoots?

While some love to poke fun at Hillsong’s slick corporate image and the ridiculous platitudes of prosperity theology, the conspiring of God with Mammon is much older.

Max Weber’s work The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, famously proposed that the capitalist disposition to earn and accumulate arose directly from the Puritan sense of calling which embraces all of life.

But now that the capitalist drive has shifted from thrift to choice, from prudence to experience, the way religion operates within capitalism has also changed.

Instead of a secularised motivation for work, the function of religion today more closely resembles those mediaeval rituals that provided sinners with the means whereby to atone for their sins.

We have our own thinly veiled forms of penance – like tithing, charitable donations, watching SBS – each of which makes us feel better about participating in decadent consumerism.

And not only that, these forms of penance allow us to participate by relieving any sense of guilt.

And so it is that capitalism and charity can cohabitate. The one lets you indulge, and the other lets you get away with it. The problem at the heart of the matter is that Christianity traditionally has geared itself to dealing with the guilty conscience of the West – how to escape from the consequences of our wrongdoing.

No wonder it has so readily been accommodated by capitalism as its ideal religious accessory.

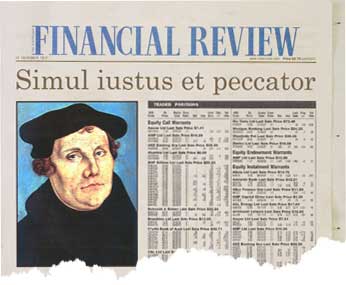

And if one person can be blamed for consolidating this state of affairs, it is the flatulent bull of Wittenberg himself, Martin Luther.

For it was Luther who provided capitalism with its religious underpinning by means of the formula, simul iustus et peccator – by faith, the Christian is at once righteous and a sinner.

He thereby secured the place for a corpulent religiosity, whose ethics are invisible but whose guilt has been assuaged by some deeply held conviction (so deep, in fact, that it never surfaces) or meagre act of charity.

When Marx claimed that a critique of capitalism must begin with a critique of religion, wasn’t he simply repeating Jesus’ warning, “Beware of practising your righteousness before other people in order to be seen by them”?

Such expressions of disingenuous charity – performed for one’s own peace of mind and in the service of Mammon – are the oil in the capitalist machine.

Perhaps the best way of breaking today’s alliance between God and Mammon, then, is to refuse ourselves the false comfort of token acts of charity and fashionable faith, so that we can see our behaviour for what it really is and dare to live differently.

Scott Stephens is an author, theologian and minister at Chermside Kedron Uniting Church. He teaches ethics at Trinity Theological College and is a regular contributor to Journey.

Photo : This is a doctored image

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline