After a veritable deluge of letters about ads for a conference and public lecture featuring Bishop John Shelby Spong appearing in Journey, we asked the Principal of Trinity Theological College Rev Dr David Rankin to tell us where people like Dr Spong have featured in church history.

IN MY VIEW, a significant number of the theological positions espoused by Dr John Spong, retired bishop of the Episcopal (Anglican) Diocese of Newark, New Jersey (USA), are inconsistent with traditional Christian teaching and received orthodoxy as interpreted and articulated, for example, in the Basis of Union.

Whether some of them can even be described as ‘Christian’ is certainly open to question.

Indeed it would not be inappropriate to classify Spong’s views on many matters of theological substance as heretical.

Spong’s views are clearly laid out in the Twelve Theses of his 1997 A call for a New Reformation (published in The Voice).

On matters such as the nature of God, the Trinity, the Incarnation, the Cross, the Resurrection and Ascension of our Lord, the place of Scripture in the life and witness of the community of faith, and prayer, he can quite properly be regarded as in error with respect to classic Christian doctrine and teaching (which Spong himself would not challenge).

My concern regarding the June and July 2007 issues of Journey was not so much about the paid advertisement promoting a speaking engagement by Dr Spong here in Brisbane, but rather several letters seeking both to discredit the Bishop and to criticise the Editor for publishing the advertisements which only managed to draw even more attention than the advertisement itself warranted.

To suggest that the acceptance by Journey of the ads indicates the support of both the newspaper and the Uniting Church itself for the views expressed by Dr Spong is wrongheaded and even perhaps dangerous.

During early church history, as the Christian Church sought to explore and define what it believed, many thinkers [such as Marcion of Pontus, Valentinus of Rome and Basileides of Alexandria (second century), Paul of Samosata (third century), Arius of Alexandria and Eunomius of Cyzicus (fourth century), and Nestorius of Antioch and Pelagius, monk of Britain (fifth)] all helped the emerging understanding of orthodoxy in the Church.

All of them – with the possible exception of the incautious Nestorius who was actually a bit of an embarrassment to both friend and foe – were devout, intelligent and deep thinkers, profoundly committed to the exploration and the proclamation of the Good News of Jesus Christ, passionate and earnest about the faith and the hope of the people of Christ.

But with respect at least to the theological questions with which they were most closely associated, all were profoundly, hopelessly and dangerously wrong.

They were and are the arch-heretics of the early church.

These faithful but misguided thinkers were important, however, because without them the fledgling Church would probably have struggled to come to terms with its God-given task of defining and articulating what it believed to be the essential content and the implications of the Good News of Jesus Christ.

It is only over against those with whom we find ourselves in utter disagreement, and in a type of dialogue with them, that we can be challenged to explore and to discover even a portion of the truth of the Gospel and the truth of God.

It might even be said that the heretics of the early centuries (and now) may possibly be part of the provisioning of God for his people – given to the people of God as an aid to exploring what we believe. For God can and does make use of error.

From time to time I have deliberately subscribed to journals which adopted positions much different from my own views so I might be forced to struggle with the lines of my own endeavours to explore a wide range of matters.

In my teaching classes now – particularly in the class on the early Church Fathers – I give over some of the time to introducing my students to some of the best thinking (in terms of clarity and force of argument) that the heretical minds of the early church could offer.

Only then can their thought, their questions (always crucial) and their answers be explored alongside those of the thinkers regarded then, and for the most part now, as the orthodox definers and articulators of the great doctrines of the Church.

Though I do not embrace the views of someone like Dr Spong, I welcome them as they better focus and sharpen our own reflections as we struggle together as church to grasp something of the truth, however imperfectly, which God speaks to us.

So Editor, please feel free to publish such advertisements without fear or favour, and feel free to mis-file those letters which are not prepared to engage the thought of Dr Spong and other controversial figures. Such activity is an essential part of the whole theological enterprise.

Rev Dr David Rankin has two doctorates and teaches in Early Church History, Patristics, and Reformation History. He is Principal and Director of Studies in Church History at Trinity Theological College

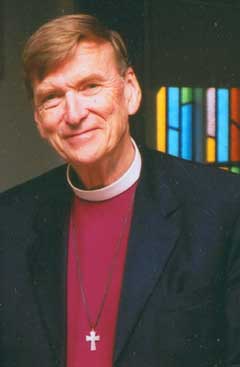

Photo : Dr John Shelby Spong

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline