April 4, 2018 marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Uniting Church minister (retired) and ethicist Dr Noel Preston AM considers the legacy of the iconic Baptist preacher and civil rights leader.

There are accolades and honours aplenty bestowed on Martin Luther King Jr.

Chief among these was the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 “for combating racial inequality through non-violent resistance”. In 1986 President Reagan declared Martin Luther King Day a national holiday. Posthumously, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom and with his widow Coretta, the Congressional Gold Medal.

For me, the most noteworthy tribute is the bust which stands high above the main entrance to Westminster Abbey as one of ten twentieth century Christian martyrs.

The passage of laws (the Civil Rights Act 1964 and the Voting Rights Act 1965), which ended official segregation and gave new rights to the descendants of slaves is the most evident of achievements of the movement King led. Millions who hitherto lived in inferiority and subservience are now empowered. Without King there would be no Obama.

How it all began

The King family, like others who grew up in his home state of Georgia, experienced the sad truth that though slavery had ended after the Civil War, segregation and official discrimination (as in the right to vote and attendance at schools for instance) was widespread across the South but also a common practice in cities of the North.

King’s role in challenging the segregation of the South began in Montgomery, Alabama where he was a young Baptist preacher. The Montgomery Bus boycott was triggered after Mrs Rosa Parks, a 43-year-old seamstress returning from a long day’s work refused to move from her bus seat for a white man. This was no planned insurrection. Rosa explained later that she was just too tired. This incident on December 1, 1955 created a protest movement in Montgomery which continued for over a year before it was resolved. More significantly, the boycott triggered a nation-wide response that challenged official and unofficial segregation.

The rocky road towards change

Often in the company of his constant lieutenant Ralph Abernethy and other black clergy of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King led numerous marches, addressed thousands of rallies, and was arrested and imprisoned dozens of times over the next 12 hectic years.

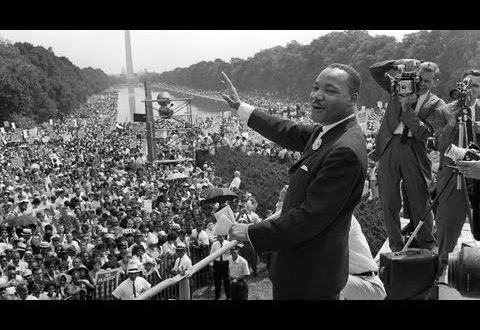

The zenith of the escalating campaign was the massive march on Washington in 1963 culminating in the famous “I have a Dream” speech. Along the way there were bombings, many death threats and many deaths. There was not only the Ku Klux Klan to deal with, but public officials such as Alabama’s Governor George Wallace and his police chief Bull O’Connor.

The Kennedy administration was ambivalent about meeting the SCLC’s demands. It was up to President Lyndon Johnson (himself a Southerner) to take the action needed. And so the Civil Rights Act 1964 and the Voting Rights Act 1965 were passed and the courts at all levels began to dismantle official segregation.

None of this eliminated racial discrimination in the North or the South. By the mid-1960s other forces began to take up the campaign: groups like the Black Panthers and individuals like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael. More and more the protest actions became violent and this was a repudiation of Martin’s absolute commitment to non-violent direct action.

The last couple of years before his assassination were disturbing. There were disputes within the SCLC and constant demands for his presence from all over the nation. As well, there were the escalating challenges of other black voices.

A deeper malady of the spirit

One of the pressures exercising King’s mind and mission in this period was the conviction that his prophetic ministry should be publicly aligned with the peace movement opposing America’s war in Vietnam. The other concern which weighed heavily on his heart was the condition of the poor, both white and black. He knew that broadening the struggle was essential for his vision of “the beloved community” which, roughly, was his translation of what Jesus meant when he spoke of “the Kingdom of God”.

On April 4, 1967, one year to the day before his assassination, he preached at the famed New York City Riverside church. He began by noting that for two years he had been silent but his conscience now left him no choice. He detailed policy changes to end America’s involvement in the Vietnam War which he said was a “symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit”. He accused the nation of taking “the young black men who had been crippled by our society and sending them to this immoral war on behalf of so called freedom when they have not found freedom in southwest Georgia and East Harlem”.

The immediate reaction was hostile, much more so than he had expected. Some accused him of cherry-picking causes because interest in the southern civil rights issues was waning. Radicals thought he was yesterday’s man, too southern, too religious and too soft. The nation’s media accused him of going too far and undermining his previous work. His relationship with President Johnson was seriously damaged. But the peace movement embraced him, and in the last year of his life encouraged him to speak on anti-war platforms.

Alongside the anti-war campaign, the cause of anti-poverty emerged as a priority. His forays into northern cities like Chicago convinced him that blacks and many whites lived in unacceptable poverty. He chose to listen to Jesse Jackson, Stanley Levison, James Lawson, “socialist church leaders” and trade unionists.

On December 4, 1967 King announced the Poor Peoples’ Campaign. They planned a Poor Peoples’ March on Washington later in 1968. He began to speak at rallies around the nation as a build up. As part of the campaign he was invited by the Rev James Lawson to visit Memphis, where garbage workers had been on a long strike for improved wages and conditions. Memphis was the location of his murder.

Drawing together the threads

Sometimes overlooked in Martin’s story is the trajectory of his prophetic mission—first civil rights, then the demand for peace and an end to the war in Vietnam, and the call to eliminate poverty which he rightly knew was a pre-condition for a just society. King developed a social analysis. He saw the connections.

King’s developing analysis of the relationship between social issues and the role of economic systems in their evolution was arguably one of the factors in the 1960s which gave global inspiration to the growth of a more sophisticated social justice awareness and commitment across Christian churches. Overlapping with King’s public activity was a period where the World Council of Churches gave a strong social justice lead to member churches while it was also a period of reform in the Vatican and across Catholicism.

In Australia in the sixties and seventies this influence was associated with programs such as Action for World Development and opposition to the Vietnam War as well as more significant support to the emerging call for Aboriginal rights.

Throughout his public life King insisted that non-violent direct action, and with it, non-cooperation with evil was the moral way to bring about change.

In 1963 King published a book of sermons titled Strength to Love. As a young preacher I regularly turned to it. More than once I used the following quotation which expresses the heart of his philosophy.

“To our most bitter opponents we say: ‘We shall match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering. We shall meet your physical force with soul force. Do to us what you will, and we shall continue to love you. We cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws, because non-cooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. Throw us in jail, and we shall still love you. Bomb our homes and threaten our children and we shall still love you. Send your hooded perpetrators of violence into our community at the midnight hour and beat us and leave us half dead, and we shall still love you. But be assured that we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer. One day we shall win freedom, but not only for ourselves. We shall so appeal to your heart and conscience that we shall win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.”

The struggle that never ends

The question we are left with is: was Martin Luther King’s dream an illusion?

It is evident that King’s dream remains unfulfilled in the USA and across the planet. Specifically, in my country Australia, there are unresolved civil rights and social justice issues including our failure to recognise First Australians constitutionally. Beneath the surface of our society, racism still lurks. Australia’s recent treatment of asylum seekers, and the electoral support for it, is, in part, racist.

The America of King’s grandchildren is still a racist society. Consider one statistic: by the early 21st century there were more black men in prison than in college. In the North and the South the crusade must still be waged that “black lives matter”.

At the time of King’s death, one of the most eloquent testimonies to his influence was given by close friend and entertainer Harry Belafonte, in conjunction with lawyer Stanley Levison:

“Martin Luther King was not a dreamer although he had a dream … under his leadership millions of black Americans emerged from spiritual imprisonment, from fear, from apathy and took to the streets to proclaim their freedom …”

Belafonte went on to recall what Martin had said in a sermon only two months before his assassination. “He wrote his own obituary to define himself in the simple terms his heart comprehended; ‘Tell them I tried to feed the hungry. Tell them I tried to clothe the naked. Tell them I tried to help somebody’.

He concluded, “And that is all he ever did. That is why … he is matchless, that is why, though stilled by death, he lives.”

The 2018 anniversary of Martin Luther King’s death coincides with Easter, as it did that fateful day in Memphis. The Easter story is Crucifixion followed by Resurrection. The one who was closest to him, Coretta, made this connection.

She wrote: “As the clouds of despair begin to disperse, you realise there is hope, and life, and light, and truth. There is goodness in the universe. That is what Martin saw as the meaning of Easter.”

King knew that bracketed within the vision is the need to act despite the cost. Perhaps the abiding lesson of these last 50 years for activist dreamers and their more pragmatic colleagues is that the struggle never ends.

As Martin Luther King famously declared, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”.

Dr Noel Preston is Adjunct Professor in Applied Ethics, Griffith University. This is an abridged version of his essay “The Life and Death of a King”. To read the full text visit noelpreston.info

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline