Karen Hitchcock’s Dear Life is a compelling and troubling exploration of Australia’s ageism problem and how our society must deal with issues around end-of-life care and the complex needs of an ageing population. Nick Mattiske reviews.

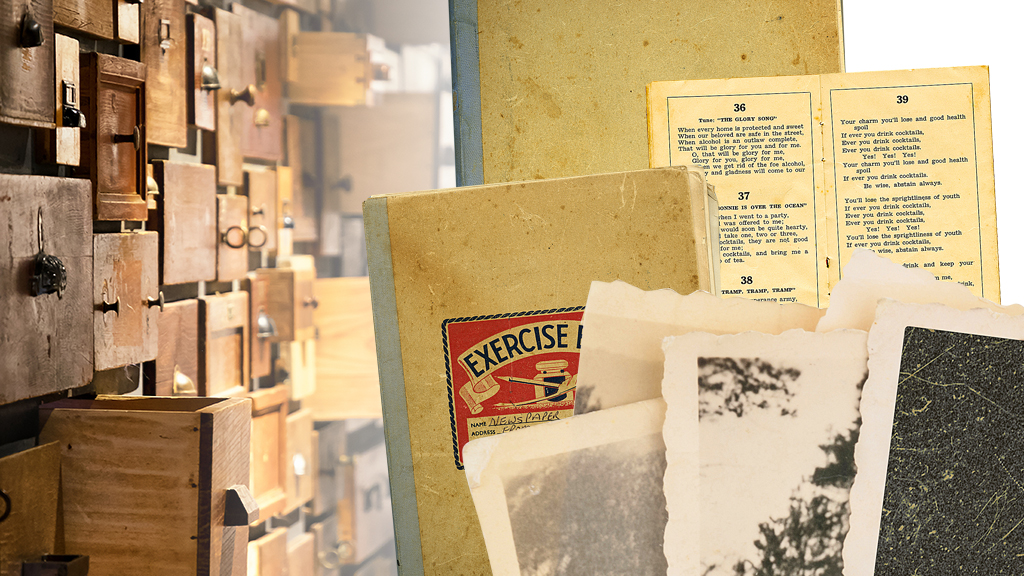

In the Bible and in traditional cultures there is a reverence for the wisdom that old age brings, but in our society increasing numbers of us are becoming fearful of growing old lest we become a “burden”, exacerbated by talk of crises in our hospitals.

But Karen Hitchcock, a doctor and writer, suggests we instead have a crisis of attitude. She describes in Dear Life the ageism built into our health care system and our society in general and asks, “Where are the parliamentary enquiries?”

She writes that the elderly regularly tell us, self-deprecatingly, that they are a burden, and we, in our coldness, actually believe them. Because we largely agree.

And so, Hitchcock writes, there is a pervasive desire to get the elderly out of hospitals so that they don’t “waste” resources. A younger person exhibiting the same symptoms that elderly patients present would not be treated the same, but hospital staff often fear elderly patients’ slow recovery rates and that the hospital may get stuck with them.

The elderly, supposedly, just keep getting sick and it becomes less and less productive to treat them. When severe symptoms present, staff are often too quick to assume an elderly patient is dying and will shunt them off into palliative care. Often, however, following the level of care we would afford any other human being, elderly patients recover like others.

It doesn’t help that the drug companies have so much invested in over-prescription. And often policy is contaminated by economic rationalism, leading to the neglect of patients themselves. But despite the rhetoric, Australia spends relatively little on hospital care and can afford to be more generous.

Hitchcock also notes that the system is hindered when medical professionals are lured into specialisation by the fat pay cheques, thereby turning them into doctors of symptoms rather than people. The book is full of harsh judgements, but by someone on the inside who can envisage, and who practises, better ways.

The attitude that the more vulnerable in society need more care, not less, set the early church apart, and arguably the Christian idea that every person is valuable has contributed to the high levels of health care we enjoy in the West. To view some patients as burdens or of less worth than others would be, as Hitchcock argues so empathetically, a dire development.

Nick Mattiske

Nick Mattiske is a bookseller and blogs at Coburg Review of Books.

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline