A 40th birthday is a time for getting out the family photos and telling stories. Dianne Jensen explores why preserving our church history is vital to the future of the Uniting Church in Australia.

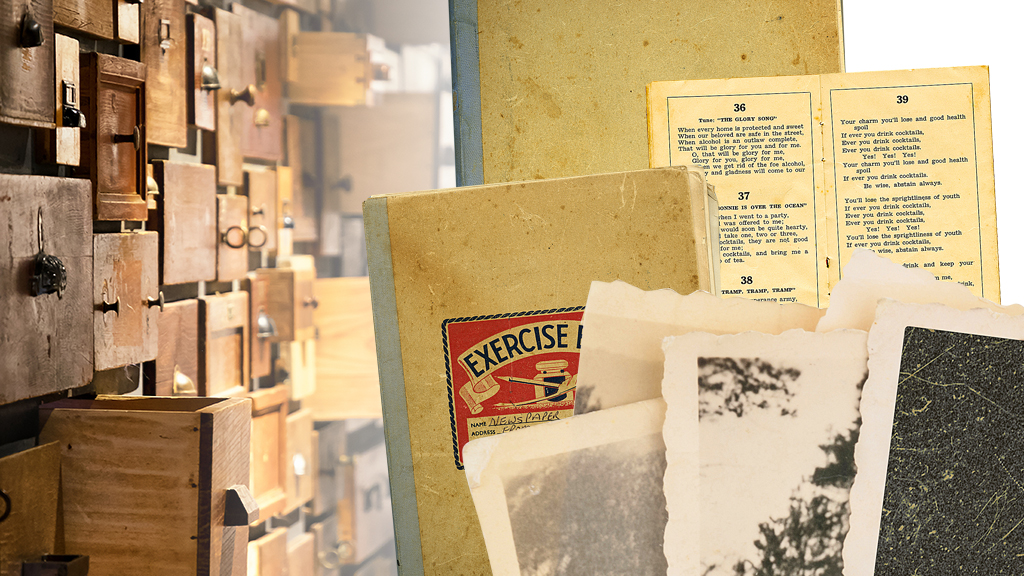

There’s treasure to be found in the nooks and crannies of our churches. Scrapbooks from the Great War, photographs of the church that was sold before union, missionaries’ letters or perhaps a tape recording of the first Uniting Church worship service.

These fragments of lived history are invaluable insights into the legacy of the denominations which formed the Uniting Church and the ups and downs of bringing people, property and traditions into a new church.

It may seem a little hasty to talk about history in a church just 40-years-old—after all, in denominational terms we’ve only just begun—but this milestone is a reminder that understanding our roots is fundamental to how we navigate the future.

The way we were

Dr Judith Raftery is chair of the organising committee for the National Uniting Church History Conference to be held from 9 to 12 June in Adelaide, hosted by the Uniting Church South Australia Historical Society.

The conference will launch a new national history association with the aim of highlighting the importance of preserving our stories and understanding our changing role in society.

“Historical records provide us with the opportunity to follow, in a methodical way, the growth and evolution of ideas and institutions over time,” says Judith. “They allow us to ask questions about their provenance and make judgements about their reliability and representativeness. Carefully analysed, they enable us to see who is advocating for or driving change and who is opposing it, and for what reasons.”

At the forefront of historians’ concerns is the passing of the generation with first-hand memories of the distinctive identity of the founding churches and the years before and after union.

“This is not, as some people might argue, a case of being backward looking or nostalgic,” says Judith. “On the contrary, it is a way of checking who we are as a church and where we are heading, and of gauging whether we are indeed a pilgrim people open to new truths.

“More than that, for newer leaders with no personal experience of the antecedent denominations, and for people coming into the Uniting Church from elsewhere, an understanding of the remnants of the older denominational cultures is vital.”

Keeper of the past

Assembly archivist Christine Gordon has been the national guardian of church records since 2001. The part-time position was created after the Assembly archives were separated from the New South Wales archives in Sydney in the 1990s, with the Mitchell Library in the State Library of New South Wales agreeing to store Assembly records.

“Apart from research, the job basically entails sorting and indexing material; preparing the records for shipment to the libraries or other institutions; putting together a catalogue of the material and making sure that our databases are up to date and accessible to researchers,” says Christine.

“Most of the Assembly material goes to the Mitchell Library, while Frontier Services (the old Australian Inland Mission) material goes to the National Library in Canberra. The collection was set up by Rev Fred McKay, John Flynn’s successor, who spent many years indexing this valuable collection in the 1970s and 1980s. Our audiovisual material goes to the National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra and we also have material in the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Studies (AIATSIS) in Canberra.”

As the main repository for the records and personal papers from the founding denominations, the Mitchell Library collections are widely used by researchers.

“The Frontier Services/AIM material, certainly up until its centenary, was well researched, although the majority of researchers request access to the Methodist Overseas Mission and the Presbyterian Board of Missions records in the Mitchell Library,” says Christine. “These organisations looked after Aboriginal missions and also the Pacific and the Asian missions, so they are widely used and widely respected collections.”

Along with some 400 boxes of material awaiting her attention, Christine is tackling the challenges posed by

the digital age.

“From 1995 to 2000 there is a lot of material which may have been lost because it was kept on old computers or old formats. I have been sent USBs with 4000 documents on them. Who is ever going to have the time to go through them and extract what’s valuable and what isn’t?”

Out of sight, out of mind?

Assembly policies lay out the responsibilities of church agencies, congregations, presbyteries and synods in terms of the records which must be kept, such as marriage registers, minutes, and financial and property records.

Historians are also encouraging churches to preserve memorabilia which reflects the fabric of church life and to gather and preserve the oral histories of elderly members.

Some synods have taken on the responsibility of preserving records beyond what is strictly necessary and making material available to researchers and historians.

“There’s really only three archivists,” says Christine. “The Western Australian Synod has an honorary archivist who works part-time with much of their material going to the WA State Library. WA has a great team of volunteers and they have been able to establish data bases and digitise the whole photo library. The Victorian/Tasmanian Synod has a paid part-time archivist and their materials are kept in an archival repository. New South Wales Synod archives have a part-time research officer and a number of volunteers based at the Centre for Ministry. Their material is kept offsite in a paid repository. South Australian Synod has its own historical society which looks after some of their historical materials.”

The state of origins in Queensland

In Queensland there is no archivist and Synod records are generally stored off-site until no longer required for legal reasons.

Most of the Queensland Uniting Church Historical Collection prior to 1977 is held at the John Oxley Library (JOL) at the State Library of Queensland.

Like other facilities, JOL faces limitations on space and resourcing and encourages a policy that keeps local archives in their original community. As part of the State Library, their emphasis is on material of significance to the whole state.

Some individual congregations such as Saint Andrew’s Uniting Church in Brisbane have established archives which include audio-visual and print, photographs, art works and artefacts.

It’s a situation which has long frustrated retired architect and dedicated church historian Jim Gibson. Jim has written two books on the history of his local Indooroopilly church as well as a photographic catalogue of churches across Australia.

He’s concerned that the lack of centralised cataloguing of Queensland Uniting Church archives, and the inability to find or access records, is allowing church history

to disappear.

“I think that our history is valuable, and it should be recorded and available for reference to know where we’ve come from and to measure that against where we are going,” says Jim.

“We are all enriched by our own sense of heritage and our own sense of what people have done before us—and it’s just so easy to lose that information. We don’t have a terrific knowledge of our preceding congregations but I think it would be a shame if we lost it altogether.”

For more information about the National Uniting Church History Conference visit historicalsociety.unitingchurch.org.au or call (08) 8297 8472.

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline