What is postmodernism and what does it mean for the life and witness of the church? Rohan Salmond explores how to live and share the gospel in a rapidly changing cultural landscape.

Forget everything you think you know; we no longer live in the modern world. We’re over it, or beyond it or whatever. Anyway, the Age of Reason is so 18th century—we’re postmodern now.

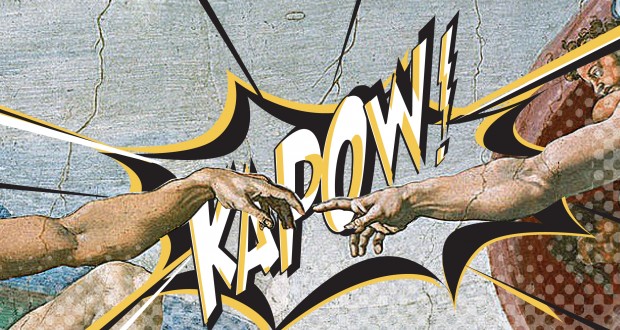

Postmodernism. It’s a hairy, scary idea that’s been lurking at the fringes of Western thought for a long time, but has now radically changed the way people relate to the world and one another. To a certain extent everyone is familiar with postmodern philosophy, architecture and art—Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans is a good example. It’s a cultural undercurrent irrevocably changing the whole of society, including the church.

But what, exactly, is it?

“It’s a critique of modernism,” says Danica Patselis, Big Year Out coordinator at Uniting College in the South Australian Synod. “It’s a critique of past ideologies rather than a stand-alone philosophy. That’s why I think it’s so hard to define.”

Rev Dr Wendi Sargeant, lecturer at Trinity College Queensland, expands further.

“The ideas of modernism were that science and our knowledge and humanity will progress and get better and better … technology and medicine would make us a kind of super race of people and we would all be gods or something like that.

“The problem came in the first and second world wars when people realised—oh no!—these breakthroughs aren’t making us better at all … So people started to go back prior, earlier in our history when we were much more interested in wisdom and looking at less of a divide between secular and spiritual,” she says.

Fewer divides is the key. Postmodernism self-consciously borrows from earlier periods and deconstructs the barriers between them. The whole modernist, compartmentalised view of the world is torn down and integrated, making the lines that separate our ideas of sacred and secular, good and evil, high culture and popular culture practically useless. That’s not to say anything goes, but nothing is quite as clear cut as it was.

This makes truth claims tricky. Postmodernism proposes that the Enlightenment idea of an objective, discoverable, capital “T” Truth was never actually real. Instead personal and cultural context must be taken into account to interpret the claim. In this way truth is actually abstract and subjective, and nobody, not even the church, has an exclusive hold on it.

“There’s a suspicion, a skepticism, on anyone’s claim to truth, and I think that’s important to acknowledge. We have to engage with that, we can’t shy away from it,” says Danica.

So what was old has become new again, except it’s been mashed up and re-appropriated in ways you probably don’t recognise.

Who the hell do you think you are?

“If you’re going to build a bridge from point A to point B across a river, you don’t find the widest stretch!” laughs Rev Dr Robert Brennan. “You find the easiest bit first, which means you’ve got to know what the other bank is like.”

Rob is minister with Graceville Uniting Church, a congregation in Brisbane’s western suburbs which meets in an elaborate, Gothic-style cathedral. The beautiful building makes Graceville Uniting a popular venue for weddings and baptisms, and many of the couples have never set foot inside a church before. It’s a great opportunity to evangelise, despite the challenge of witnessing to people who hold a radically different worldview.

“A Baptist friend was telling me the other day, this old school evangelicalism which says, ‘Preach the law until conviction comes, and then preach grace until conversion,’ that doesn’t work anymore. And you know, he nailed it,” says Rob.

“A lot of the old methods of proclaiming the gospel are about convincing someone they’re a dirty rotten sinner, but these days if you tell that to a postmodern—in whatever polite way you can say that— they’re going to look at you and say, ‘Who the hell do you think you are?’ ”

The postmodern worldview may be skeptical of truth claims generally, but claims made by elite organisations like churches and governments are particularly suspect. These powerful institutions have historically imposed their worldview on others through coercion, control and colonialism, so they are no longer seen as trustworthy. To overcome this skepticism, trust must be built relationally, person-to-person.

Rob’s unusual ministry placement has prompted him to research what makes people with a postmodern worldview tick. His article, “What does evangelism mean in a post-modern society?” appeared in the July 2014 edition of ACCatalyst magazine, and his research continues.

“When you’re sharing good news with people you have to think about what they think is important,” says Rob. “You really have to connect with the people around. That’s really at the heart of where I’m at.

“If you pick up issues of fairness and justice, that’s what a lot of the younger generation are about.”

Into the wild

It’s an unfamiliar landscape for many churches, which for more than 200 years have grown accustomed to the respect previously afforded to institutions, and the power that gave them to set the cultural agenda. But Wendi says the postmodern cultural landscape gives opportunities as well as challenges.

“I think in a postmodern world many, many more people are much more interested in faith than we think. Back in modernity you were either in or out, but now there are a lot of people who might be a little bit in, a little bit out—they are interested. They could be engaged.”

Adapting is hard, but it helps churches rediscover parts of Christian faith that fell out of favour during the modernist era. Danica Patselis describes her experience exploring ministry with young adults with a postmodern worldview.

“In my experience, they really do believe that we need to take our faith outside of church, take the altar into the community, and that we actually create places of mission and ministry outside of the old frameworks, so outside of Sunday, outside of those places.

“They want everything to be integrated. They want it to be authentic. They want it to be transparent. They want to do ministry every day, in their workplace, in their school—they’re seeing those as sacred places, and sharing the message of Jesus and the hope and love that he brings.

“It’s taking it out, doing what Jesus did and going out into different contexts and gathering people around to listen to their reflections as well.

“So that’s where I see postmodern ministry. I don’t think it’s a reshaping just of the Sunday service, it’s a total rethinking of the whole of life.”

And yet, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

“It’s not that our core doctrines change,” says Wendi. “It’s our way of presenting those doctrines, or the way we tell the story. It’s going to be necessarily different because of the difference in the world.

“I guess I would embrace postmodernism—not necessarily all of it—but I think God is bigger than our philosophical categories.”

Danica says, “The centrality of who Jesus is, is really important. In this postmodernism, and when I talk to my non-Christian friends, I think that’s one thing I don’t want to be confused by.

“I think if we centre ourselves on Christ, it doesn’t matter what the thought or philosophy or new era of being is, Christ will always be the greatest revelation amongst that.

“We can firmly proclaim that Jesus is the Incarnation, the head of the church and the best example of someone who took the altar out into the community and listened.”

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline