As the seasons of the church’s year bring us around again to Easter, we are given a renewed opportunity to again enter into what for the Christian faith is the heart of the whole Judeo–Christian tradition.

Pared to what could be described as observable, we have a Jewish rabbi who wants renewal of the faith of his people; a few motley followers, who have their own agendas to varying degrees; what appears to be a calcified and reactionary religious leadership, fearful of the loss of their own power, concerned about keeping the occupying power from destroying their people; and an occupation force that seems mostly indifferent, wanting only to keep some kind of order so that they can continue to feed the beast of empire.

Yet Christians believe that in this drama, ultimate truth is revealed—the truth about humanity, God, and destiny of creation. Two millennia later, this drama is still informing the lives of billions of people, and across the globe, people are encountering it as a way to interpret the mystery of their own lives.

The Easter story has echoes back to the creation myths of Genesis, particularly the first story, in Genesis chapter one. Here, it’s widely recognised, Jewish faith responded to other cultures’ stories that validated violence as an integral part of the order of the world from the beginning by rejecting that view and asserting that the world was created as both orderly and intrinsically good—in a state of peace, of shalom. Jewish faith introduced the idea of humanity living now in a state of having fallen from an ideal, ordered, non-violent state.

The work of the French anthropologist Rene Girard highlighted the embedded place of violence in the current ordering of human society. He also pointed to the Easter story as a repudiation, uniquely so, of that current ordering.

At Easter, we celebrate the negation, and the revelation of its futility, of human violence as a way of ordering human life. We believe that creation is restored in Jesus by his willingness to absorb the violence directed at him; the human violence that is a part of all of us.

The Apostle Paul in his letter to the church at Corinth, highlighted the strangeness of our confession: “Jews demand signs, Greeks desire wisdom, but we proclaim Christ crucified … Christ the power and wisdom of God.”

Jesus’ self-offering, affirmed by his resurrection, showed that the powers that we fear, and that we all too often follow, in ourselves and in others, are not final, nor of the order of creation. They are not natural.

He overcame sin and death by this radical commitment to the ways of the God revealed in the story of Israel. Life now presents to us a wonderful vision and some profound challenges—about not living to our fears, and about living faithfully to the one whose life is vindicated by resurrection.

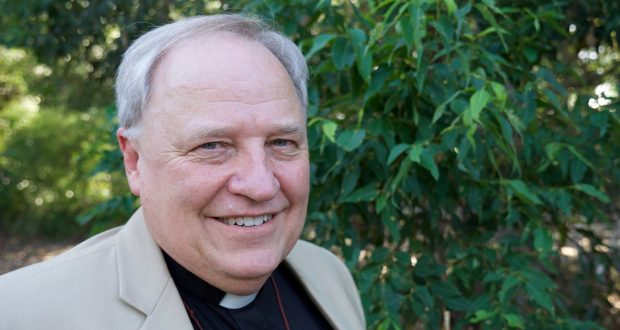

Rev David Baker

Moderator, Queensland Synod

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline