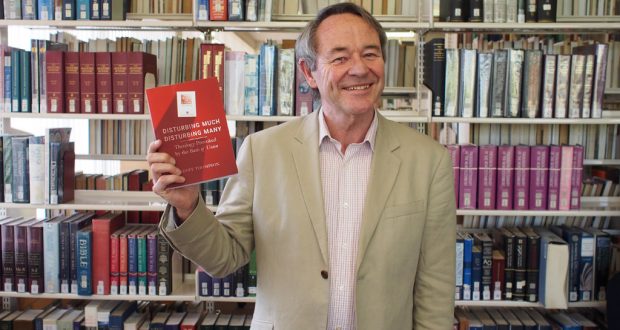

Here in Queensland to promote his new book, Disturbing Much, Disturbing Many: Theology provoked by the Basis of Union, Rev Dr Geoff Thompson sat down with Journey to delve deeper into issues of faith, society and the Uniting Church in Australia’s foundational document, the Basis of Union.

Journey: If there’s one takeaway from the book, what is it?

Geoff: The Basis of Union points to Jesus Christ as the foundation of the church, and as the foundation [of the church] he is a disturbance to the church.

How so?

Because he’s strange.

Strange in what ways?

In a number of ways. The way the Christian church makes the identity between Jesus and God unsettles many of our received cultural views of God, not just the God up in the sky, but God who is understood only as power or only the source of blessing; Jesus Christ is one who shows us what God is like through abandonment; suffering; powerlessness; and this, in a sense, is not what God, culturally understood, is supposed to be.

Who is your book for?

Firstly Uniting Church folk. To be honest it’s mostly pitched at people who already have some theological understanding or people who have begun to ask theological questions. I would hope that the book is sufficiently accessible for them too.

One of the really important things I want to say about the book is that it’s not an exercise in retrieval of the Basis. There’s some books that have been written which expound the Basis, and tell us its history.

What I’m trying to do is say this is the theology we’ve got, and to ask what do we do with it. I try to use the Basis as a springboard for thinking about and engaging some of the issues that are alive in the church today.

Can we relate that disturbing sense of God to our current political space, particularly around asylum seekers?

I think I can see some connections there. The dominant political narrative about refugees and asylum seekers is about protecting ourselves, and I think it’s also true to say that that issue aside, the church has a history of protecting itself, whatever the forces might be.

I think the Christian church is always called, not to protect itself, but to actually protect others and to care for those outside the church in the same way that Jesus cared for all those he encountered.

So I think the church is called to let go of being concerned about its own security, its own stability, its own safety in our particular culture, and in that way it could be an example to a nation that is diminishing itself by the way it can only think about protecting itself from a threat that arguably doesn’t even really exist.

You touched there on protecting ourselves versus what we as Christians are called to do. That’s a dangerous idea. When you change that thought process it’s pretty disturbing. Is that what you’re trying to get across in your book?

I think so. Again it comes back to the narrative that the New Testament witness itself proclaims about Jesus. That he was someone who did not fit categories (and I talk about this in the book) in the way the early church’s message about God was so strange: worshipping someone who’d been crucified on a cross by the powers of the day, and crucified as a criminal; worshipping such a person as God was so radical that it actually drew forth charges of atheism.

Christians were accused of being atheist because their discourse about God was so strange and they were subverting not only the political, but also the religious norms of the day.

I think the Basis of Union tries to reacquaint us with this strange Jesus, it talks about how he comes to us ‘in his own strange way’. The moment you put Jesus at the centre of all the different topics of Christian theology and of the issues that we’re discussing and living into in the church today, we find that some of the traditions that we’ve actually received, the conventional ways we approach things, actually get disturbed.

And in one sense I want to suggest that’s the constant state of the church, of being disturbed by its very foundation.

This is a paradox. Where do we get our security from? It’s not from the culture, it’s from Jesus Christ, and yet he is of such a character that he disturbs us out of complacency and fear.

Is it possible for large institutionalised churches to be light-footed and flexible?

One of the things I say in the book when I address this very question, is that the challenge for the church is not between being a movement and an institution, but it is to be a flexible institution without becoming institutionalised.

There’s nothing wrong with being an institution but it’s about how flexible we can be.

I quote an American sociologist, Richard Sennett, who talks about how all the radicals of the 1960s were all about creating community and disrupting all of these institutions, he said they did disrupt all these institutions but what they got was complete fragmentation of society. Sennett says societies actually need some sense of coherence and mutual accountability which, properly used, is what institutions actually do.

But when you reach a point of being institutionalised then you lose that flexibility and dexterity.

Is part of the solution to being more flexible and light-footed to remember that as per the Basis of Union, the Uniting Church is a movement for Christian unity rather than an institution?

That’s one of the constant dangers for us. I’ve bought into this as much as anyone else; we can so focus on the identity of the Uniting Church that we actually become another denomination, and I suspect we actually have. Part of our challenge is to somehow let go of that.

The issue of placing Jesus Christ, this strange unusual God-figure as the foundation of church, actually has profound implications for a whole range of theological topics, and the ones that I’ve addressed in the book are spirituality, the Bible, baptism and the Eucharist, sexuality, scholarship; all of these things around which we have quite conventional ways of talking, I think when we really are deliberate about saying, ‘what difference does it make to these issues’ if we argue that Jesus Christ is not only the foundation of the church but the starting point for our discussion about those issues, then we find ourselves disturbed.

In the future what would you hope and think the 2000–2020 period of the Uniting Church will be known for?

I think it will be known as a time of intense questioning about our core vocation and our identity as a church. I think we will be known for a church that becomes more aware of our intercultural nature. I think in which the challenges and the struggles of the covenant with the Congress will press itself more and more upon the church; I hope that in all of that we will also re-familiarise ourselves with the core convictions that brought the Uniting Church into being because I think they remain as relevant to all of those issues now as they were back in the 1970s.

The conviction that grew on me as I was writing the book was that it’s often thought that when you talk about the centrality of Jesus Christ you’re making a very conservative statement, reinforcing the status quo. I’m increasingly convinced, however that not only does that starting point always call into question the status quo, it’s also something that’s very fruitful and productive. I hope that by re-familiarising ourselves with that starting point we can become a church that sees the world more clearly through that filter.

Disturbing Much, Disturbing Many can be purchased from Morning Star Publishing. It is also available for loan at Trinity Theological Library.

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline