Singles make up more than half of the people in churches, yet they are often sidelined when it comes to ministry and outreach. Dianne Jensen asks singles how we can change things.

Many people go to church alone. While some have a spouse tucked up in bed with the Sunday paper or doing the soccer run, others attend by themselves because they are single.

The proportion of single people in Australia (never married, separated or divorced, widowed) now outweighs those who are married. Data from the 2011 census gathered by the Bureau of Statistics shows that 48.7 per cent of the population aged 15 years and over are married, down from 49.6 per cent in 2006. While these numbers do not take account of the 11 per cent of Australians aged 18 years and over living in a de facto relationship, it seems reasonable to assume that singles probably outnumber marrieds in the average church congregation.

What does this mean for church communities? Clearly, if churches are framing their worship in terms of couples and families, the majority of those sitting in the pews may be wondering if they are invisible or simply keeping the seat warm. In terms of outreach, churches may be ignoring an entire segment of the population in their desire to attract families.

We all know that singles don’t come in neat categories. Never-married, divorced/separated and widowed are diverse groups distinguished by age and personal circumstances. The unmarried professional has different concerns from the young widower or the recently divorced retiree or the elderly person grieving their life partner.

Singles are not universally lonely or unfulfilled, and most are not pursuing a call to the celibate life. What they do have in common is the desire to have their life experience and their spiritual value affirmed by their church community.

Are you here alone?

Katherine Grocott, in her dissertation A singular focus: theology of singleness (2005) points out that the church has had a pendulum swing in regards to singleness.

“The reformers of the sixteenth century had to work very hard to justify marriage because the church, from its early days through to their own time, had held celibacy in such high regard,” she writes.

Although Jesus and Paul describe both marriage and singleness as gifts from God, the elevation of marriage as the norm and a sign of God’s blessing effectively cast a shadow over singles.

“Many parts of the church view singleness as second best, a disappointment and not God’s will for a person’s life,” says Katherine.

A straw poll of Uniting Church singles—each serving their local church in a variety of ways—suggests that this is indeed the case.

“One of the challenges about being single in Australian society in general, and the church in particular, are the assumptions that people make about your singleness,” says a professional woman in her early sixties who has never married. “They include such assumptions as you have not met the right person yet, you are gay, you’re obsessed with your career, you do not ‘want’ children and the like.”

These negative attitudes impact all single people, she adds, including those who are separated or divorced or widowed.

“In all these circumstances a single person is often treated with suspicion (e.g. if a single woman, you are not to be trusted—by both women and men—to be in the company of married men) and awkwardness (e.g. not raising topics of conversation that the speaker deems not to be ‘appropriate’ for a single person).”

Table for one please

Couples often feel awkward around those who have lost partners, once their initial sympathy passes. A retiree who became a widower many years ago remembers feeling isolated by his church community.

“People tended to avoid me. It was only much later I found out why, that they were coming to terms with my wife’s passing and also just did not know what to say to me. Once I understood this I did not feel quite so disappointed.”

Another congregation member, now in her 80s, continues to feel that the loss of her husband has rendered her invisible at church.

“If I go to a church function, I find all the couples gravitate to their own table, leaving the single people to get together as though we are only of interest to other widows and widowers.”

For the divorced person, their single status evokes a complex mix of responses.

“Each person brings uniqueness to a congregation and should be recognised as who they are, not who they are married to, or how many children they have,” says one woman, who has learned to keep her answers brief when people start to probe.

“I don’t think many people are single by choice. Who wants to go home alone all the time?”

What not to do

Ministering to the needs of this disparate group presents a number of challenges.

United States pastor and author Adam Stadtmiller, writing in Christianity Today’s Leadership Journal (2012) says that a study of singles ministry yields common themes about why programs targeting singles often fail.

“The problem was not the intention, but the core concept that singles’ needs are best ministered to in a segregated setting. This led to ministry models that actually disenfranchised singles from the body of Christ and isolated them in groups unable to maintain long-term structural and emotional sustainability,” he writes.

“While I agree that singles have unique needs, I have a hard time finding any that the church cannot address in a mixed setting, provided that the church is on mission to integrate singles into the entirety of church and body life.”

With the exception of support groups and social networks, the singles Journey surveyed did not want to be “ministered to”.

“I prefer an inclusive church where the church works harder on creating and sustaining models of ministry related to bringing people together, identifying the commonalities and ‘making difference ordinary’,” says one respondent. “I think one of the problems of the 21st-century church is that the church operates by creating groups and silos, where territory is marked out, topics are reduced to binaries, and the complexity of issues and the multiple perspectives that can be held are simplified, and/or discounted and/or obscured.”

She adds: “I do not see singleness as a calling or as a gift to the church. It is a state of being. I want the church to affirm my life and how I live it with and through God’s grace. I want the church to affirm this for all people without categorising or labelling us.”

We’re all in this together

Everyone agrees that one thing that the church can provide is community.

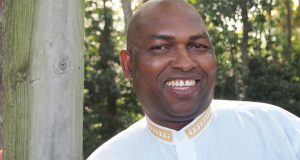

Simon Gomersall is the pastor at Toowong Uniting Church in Brisbane, an established congregation whose broad congregational demographic reflects its close proximity to university campuses and the city.

“Here we think in terms of family, rather than families. That is at the heart of our identity as a church,” says Simon. “We are all in this together as disciples of Christ, and there are families within that and there are also single people and perhaps other formations of relationships.”

The pastorates (mid-sized groups) at the church are created according to convenience rather than age, marital status or interests.

“What we found is the ones that flourished were the ones that had numerous generations within them and there’s something healthy about that—the singles meet the marrieds and the younger people meet the older people and vice versa,” says Simon.

“We are so captured by the ideas of the culture around us, you could almost say that marriage can become an idol in western society because it’s what people look to, believing that it’s going to provide them with their ultimate sense of meaning and purpose … whereas our faith acknowledges that marriage is a good thing and a valuable thing, but we are pointed beyond it to another relationship that will actually provide the ultimate meaning and purpose.”

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline