As the Uniting Church celebrates its fortieth anniversary Ben Rogers revisits the excitement, challenges and hope behind the historic union of Congregationalists, Methodists and Presbyterians in Australia in 1977.

For younger members of the Uniting Church in Australia who have only ever known its current incarnation, the period surrounding church union in 1977 is past history.

Visiting Wikipedia’s rundown of the most notable events to impact Australia in 1977, you’ll see the Uniting Church’s formation listed alongside the nation’s worst railway disaster at Granville, the birth of the Australian Democrats party and Sir Joh’s Queensland government banning street marches.

It was a year when theatregoers experienced a new science-fiction vision in Star Wars, “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” topped the Australian music charts, World Series Cricket began and Melbourne saw the arrival of refugees from the Vietnam War. But for many Christians it marks the birth of an Australian church called to bear witness to a radical vision of Christian unity that rose above cultural, economic, national and racial boundaries. This new church was a pilgrim church, called to follow and preach the risen Christ.

Rachael Jacobs, writing for The Sydney Morning Herald on how 1977 changed Australia forever, sees the Uniting Church’s launch as one of the year’s key milestones: “[It] created not only a new denomination, but a movement.” In fact, the Uniting Church’s foundational document, the Basis of Union, insists this new church was to be a “movement for Christian unity” rather than just another denomination.

Are we there yet?

Union was a highly risky move for denominations which had developed their unique identity and traditions over centuries. But the timing was right for the generation who had witnessed the carnage of the Second World War; they saw an opportunity to build a new church shaped by the hope and energy of twentieth century Australia.

Nevertheless, for those who experienced the years leading up to union, the early seventies was a period of mixed emotions as each denomination worked through its own process.

Rev Dr Norma Spear, the first woman ordained by the Methodist Church in Queensland, remembers many Methodists feeling a tinge of apprehension as to how it was all going to work. There was also a sense of inevitability due to the Methodist Church’s all-or-nothing vote on whether to join the Uniting Church.

“There was no congregation who had a right to stand aside. Some people felt that as the Presbyterians were having that right, they felt a little bit disadvantaged or

put out because of that. But basically there was a sense

of ‘This is the way it was going to go’.”

Rev Dr Andrew Dutney, immediate past president of the Uniting Church, was in his late teens at the time of union and says, “The union itself should have happened in 1974 or 1975 but it got dragged out because of a problem with voting procedures and then a series of court cases, disputes over property and things like that between people who were coming into union and those who weren’t.

“So the whole thing got delayed, so there was a sense of, amongst some people, frustration. Others were a bit over it and there was a general feeling that it should have happened earlier.”

Andrew remembers for the Presbyterians it was a much more painful process as some chose not to join the Uniting Church, fracturing friendships and communities.

“We were aware that a couple of the big Presbyterian churches with youth groups were not coming into the Union so we were also negotiating those relationships and that was really tricky because there were people, some of my closest friends from those days, that I basically never saw again after union, and it wasn’t because we had a falling out or anything like that; it was just our paths went in a different way and so that was kind of weird.”

A winter’s tale in Milton

Although preparations for union presented a number of practical challenges such as property arrangements and ministerial placements, there was a strong sense of anticipation and camaraderie as the inauguration

drew closer.

“We were doing something significant as Christians,” says Norma. “Really trying to show that sense of unity that we have among ourselves, rather than the sense of division that allowed people to almost become isolated in their own little areas.

“I think it was interesting getting to discover that the people of the other denominations were very much the same as us. Some of the things that we had to surrender for the sake of union, though we may have held them as very important, they were not as important as becoming united.”

That unity would be officially inaugurated at the Sydney Town Hall on 22 June 1977 and Rev John Mavor, former Queensland Synod moderator and Uniting Church president, was there to witness the festivities.

“One of the general secretaries gave my wife and I tickets to the Town Hall, they were as scarce as hen’s teeth,” says John. “It was a great night with a choir, good preaching by Rev Dr Philip Potter from the World Council of Churches; a great occasion. People who couldn’t get into the Town Hall were all waiting outside.”

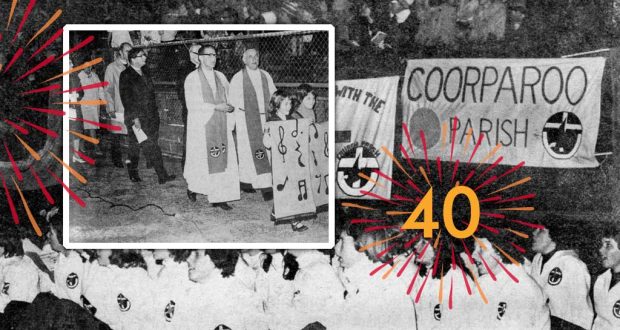

For those celebrating in the Sunshine State, the main event was held at the Milton tennis courts in Brisbane led by the Queensland Synod’s first moderator, Rev Rolland “Rollie” Busch.

Rev Don Whebell—former two-time Queensland Synod moderator and lecturer in the Basis of Union at Trinity Theological College—takes up the story.

“The gathering at Milton tennis courts was treated to bitterly cold weather, and a lot of razzamatazz music and bitty presentations about what a great thing it was to be here. One of the central pieces was the sermon by Rollie Busch. After all those years, I can still hear his encouraging words about following Christ into a fresh, new future.”

“It was a time when what was the then younger generation would be involved in a great step forward for all churches—and we Congregationalists, Methodists and Presbyterians were involved in it.”

Similarly, for Andrew, talk of the Milton celebrations brings back reminders of Rollie and the winter chill: “I remember it was really cold at the Milton tennis courts, freezing cold, as it should be in the middle of winter in the open air.”

“My enduring memory was of Rollie Busch who preached on the occasion and who led the celebration. His personal excitement was so tangible, so palpable, it was like there was a light inside him that was bursting out and I just couldn’t take my eyes off him.”

Walking the walk

In the immediate aftermath of the inauguration, congregations began working through the reality of creating new communities of faith.

“The hymn book was a big deal,” Norma recalls. “Fortunately the Australian Hymn Book was published around that time so we took that on. I think the way in which it was handled meant that people appreciated what it meant for the other congregations not to have to sing out of a Methodist hymn book.”

Andrew notes the matter of ministerial terms inspiring a generous act of fellowship. “At Union, elders in the Presbyterian churches were entitled to remain elders in the Uniting Church for life even though after Union, elders were to be elected for three-year terms.

“I’m aware of one congregation where the elders in the Presbyterian congregation all resigned at the time of Union and made themselves available for election on the three-year basis, so they put themselves willingly on an equal footing with formerly Methodist leaders.”

Back to the future

As the church celebrates its fortieth anniversary, what can we learn from 1977?

While John Mavor acknowledges that “we’re in different times” now, he points out that the value of patience and hard work endures.

“It took a long time for church union to come to pass. People worked at it for a long time. Too often in the church we want things to happen straight away. In the church union they worked for it, they planned for it and we had strong leaders who were speaking for it across the life of the church.”

For Andrew Dutney, the spirit of excitement felt in 1977 is crucial for the life of the church moving forward.

“From 1977 onwards for the next few years, there was a really strong sense of being a movement more than a denomination,” says Andrew.

“I think we could use another dose of that about now; that sense of being part of an exciting movement even though we’re in challenging times.”

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline