The Intervention has caused controversy since its introduction, and Indigenous Australians are calling for genuine respect and partnership. Rohan Salmond explores.

At the Uniting Church in Australia’s 13th Assembly, members of the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress (UAICC) told their stories about what it is like living under the Stronger Futures legislation in the Northern Territory. The Assembly was moved to action and made a public demonstration on the steps of South Australia’s Parliament House. Now, from 17–23 March, Uniting Church members across the country are asked to undertake a week of prayer and fasting for justice for Australia’s First Peoples.

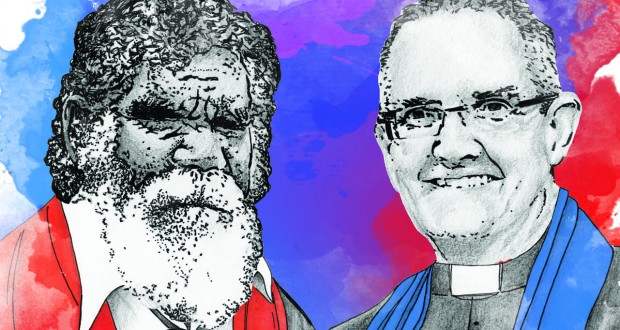

“The Uniting Church has a very long tradition of solidarity with Indigenous people,” says Uniting Church President, Rev Dr Andrew Dutney, “but we need to go deeper in that solidarity and recognise our Indigenous members are indeed part of us; they are not a ‘them’, they’re not the objects of our concern, we are a community.”

On 18 March the Uniting Church will host a public vigil on the lawns of Parliament House in Canberra. All Uniting Church members are invited to attend.

“Stronger Futures”

In 2007, in the face of a looming federal election, the Northern Territory government released the Little Children are Sacred report, an inquiry into child sexual abuse in Aboriginal communities. In response, the Howard government implemented a package of legislation without consulting the Aboriginal communities it affected. The flagship bill was the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Bill 2007 (NTNER) and the package of legislation became known collectively as the “Intervention”. The bills received bipartisan support, and have since been replaced by Labor’s Stronger Futures policy. Stronger Futures renewed and expanded the key components of the Intervention.

The lack of partnership between governments and local communities is the root of the problem with Stronger Futures. In a submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs in 2012, Ŋalapalmirr Elder and Uniting Church Minister, Rev Dr Djiniyini Gondarra spoke on behalf of the Yolŋu Nations Assembly.

“The issues of alcohol abuse, violence, sexual abuse, disease, chronic illness, child mortality, life expectancy, overcrowding and poverty are not barriers [of disadvantage]; they are symptoms. Instead, the barrier is external control, either on a systemic level or by the domination of mainstream culture over Indigenous culture,” he said.

A licence to discriminate

Ninety per cent of people on income management in Australia identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

One of the greatest concerns with the initial Intervention in 2007 was its exemption from the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (RDA). By circumventing the RDA, the measures contained in the NTNER Bill—particularly income management measures—were able to be applied to Aboriginal communities without affecting the rest of the Territory. Income management is a set of measures which quarantines 50 to 75 per cent of a person’s Centrelink payment for “priority needs” such as housing, food and clothing. This money is channelled into a “BasicsCard”, which is only accepted at a limited number of participating shops.

Brooke Prentis is an emerging Aboriginal Christian leader and Coordinator of the Grasstree Gathering, an ecumenical conference for emerging Indigenous Christian leaders from across Australia. Although she is from Queensland’s southeast corner and has not lived under the effects of the Intervention directly, she says all Australians should be paying attention to the stories Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory are telling.

“I think the broader concern is really the way the legislation was passed through the Commonwealth Government. When the Northern Territory Emergency Response went into place, the Racial Discrimination Act was suspended. The fact the Parliament can suspend such an important piece of legislation that protects Aboriginal people and other people … is a concern for all Australians,” she says.

The expansion of the Intervention under the Stronger Futures policy has since brought income management back under the RDA. However, upon the reinstatement of the RDA in the Northern Territory in 2011, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner Mick Gooda suggested that income management was still in breach of the RDA due to its disproportionate impact on Indigenous people. In the 2013 Parliamentary Library Background Note, Income management and the Racial Discrimination Act, the Parliamentary Library agreed the BasicsCard scheme was vulnerable to challenge. However, as yet no formal challenge to the scheme has been made to the Australian Human Rights Commission.

Brooke is concerned at the scheme’s expansion into other parts of Australia. In Queensland, as of February 2014, the BasicsCard has already been rolled out in Cape York, Rockhampton and Logan, south of Brisbane with further expansion on the horizon.

“As Aboriginal people [in Queensland] it’s affecting our brothers and sisters in the Northern Territory, but it also has ramifications for us here,” she says.

Income management does not represent the entirety of the Stronger Futures policy, but it does capture the essence of the tensions surrounding the larger suite of legislation: some people find it helpful in their situation, while for others it is profoundly disempowering.

“Parenting/Participation” income management is the primary form applied through the Intervention measures.

A destiny together

The UAICC is outspoken in its condemnation of the process the Federal Parliament undertook to introduce the Intervention legislation in 2007. Unfortunately, the current Chairperson of the UAICC, Rev Rronang Garrawurra was unable to comment for this story due to illness, but is expected to be well enough to attend the vigil in Canberra. Other UAICC members in the Northern Territory able to speak to the issue were also unable to be contacted due to their remote location.

Northern Synod Moderator and Assembly President-elect, Stuart McMillan is clear he is unable to speak on behalf of the Indigenous members of the Uniting Church. However, responding to the Northern Territory Intervention has been a priority for the Northern Synod since the introduction of the NTNER Bill in 2007.

“The Indigenous members of this Synod have said the same thing since 2007 to Territory and Federal governments alike,” says Stuart, “They seek a different form of engagement and a genuine coming together to seek solutions to issues. They ask that governments stop doing things to and for them and engage in a way that might better be described as partnership.”

In his 2011 submission, Djiniyini called for the end of Indigenous disempowerment. “My people have one policy for our own development. Self-determination,” he said. “We await the day when the Australian Government meets our various invitations and negotiates a treaty with our tribal governments. From that day forth we can then begin our journey together as true partners.”

Prayer and fasting

The Uniting Church’s response to the Intervention might come as a surprise to some members. Although fasting is practised by some individuals in the Uniting Church, it is uncommon to see it practised on a broader scale.

Andrew Dutney says fasting is a very biblical response.

“In scripture fasting is often provoked by something very significant that’s happened: there’s been a death, people are afraid, people are searching for a direction or the community is about to launch into something new. They almost automatically go into a period of fasting while they seek God and plead with God to give them strength and guidance and blessing for this next thing that they’re going to do.

“It’s my hope that [after the fast] the Uniting Church will have a much stronger sense of being one body of Christ. That’s my primary hope.

We’ll have a much stronger sense of being the one body of Christ which is focusing on those members who are most disadvantaged and most vulnerable in our community and frankly, those are our Indigenous members.

“It’s as Paul says, ‘If one suffers, we all suffer together.’ It’s high time we felt that as part of our identity.”

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline