In the 21st century what should Christians make of the concept of “sin”? A long-gone relic or a necessary corrective in a society seduced by moral relativism and the cult of victimhood? Simon Gomersall explores sin, Easter and atonement.

It is now conventional to assert that the language and concept of sin is irrelevant in both 21st century Australian society and church. Society has moved beyond sin.

The church finds the concept quietly embarrassing. A by-product of western society’s journey from theism (belief in a living God integrally involved in his creation) to deism (belief in a distant God merely watching a self-contained world) to naturalism, pantheism and a variety of other “isms”, has been the shedding of previously assumed moral categories.

If God is redundant, or worse, non-existent, then humanity inevitably becomes its own frame of reference in moral and ethical thinking.

Alistair McFadyen—author of Bound to Sin—set out to explore the Christian notion of sin in a society where pragmatic atheism (even if we believe in God, we live as though we don’t) has the narrative advantage. He acknowledges the church’s complicity in this state of affairs, referring to the legitimate “suspicion that sin is a language of blame and condemnation encouraged by its flourishing in religious enclaves where it is used to whip up artificial and disproportionate senses of personal guilt and shame.”

God-talk—let alone sin-talk—seems superfluous to the conversation we use to make sense of the world and our place in it. Suspecting that psychological, sociological and philosophical language carried inadequate explanatory power to describe concrete pathologies at work in the world, McFadyen explored two phenomena which he found everyone agreed were categorically wrong: the holocaust and child abuse. Beginning from these existential reference points, unpacking the nature of the events, he concluded: “Sin is an essentially relational language, speaking of pathology with an inbuilt and at least implicit reference to our relation to God.”

So perhaps there is a relationship between our capacity to see currency in the concept of sin and the degree to which we are attentive to and dependent on God?

To be sure there are numerous biblical words and images within the conceptual boundaries of “sin”. The most common New Testament word used to describe “sin” is hamartia, which means to “miss the mark”. An archer shoots an arrow and misses the target.

Another is parabasis which means to “transgress or trespass, stepping beyond a forbidden boundary”. Another is anomia, often translated as iniquity. This word means “without law”, implying the rejection of a prescribed regulation.

Asebeia (ungodliness) means literally “no worship”, living without any reference to a Creator; parakoe (disobedience) means “refusing to hear”; opheilema (debt) speaks of owing to another some degree of obligation. At even a casual glance, these are strongly relational images and make little sense without an active deity setting targets, drawing boundaries, inviting worship, speaking guidance and entering into social contract.

English theologian Alan Mann (author of Atonement for a Sinless Society) explores the impact of the loss of moral categories for contemporary society: “The stories we tell seldom, if ever, attribute sin, guilt or wrongness to ourselves. In turn, geneticists, sociologists and psychologists increasingly legitimise our narratives and allow us to live in the confidence that we do no wrong.”

Mann goes on to describe the “cult of victim” gripping the western imagination. It is always someone else’s fault: our parents, teachers, the government, or increasingly the church. Philosophically, we assume the postmodern virtue of prescriptive relativism (that the presence of difference denies the affirmation of particular ideas or behaviours over others). All views are equally valid. We each define our own morality. What is right for you, might not be right for me.

As young people are assured that classifications of right or wrong are relative and personal, they are simultaneously bombarded through electronic media with pervasive images of personal ideals: visually attractive, socially competent, vocationally successful, compassionately altruistic.

They end up being torn between an artificially created ideal self and their real self. They are told there is nothing wrong with them, yet they live with a persistent and niggling feeling that they are falling short of something. When our real self never matches up to our ideal self, instead of feeling guilty (no need to, because there is no moral standard to transgress) we instead live lives of quiet desperation and shame. Shame is a powerful emotion. It drives us into a self-imposed isolation from God, others and even self to cope with its internal dissonance.

What we need is “atonement” (at-one-ment). We need to be made whole. The disparate parts of our “self” need to be woven back together alongside our relationships with others and, foundationally, our union with God.

Ian McEwan’s novel Atonement translated into film in 2007 (starring James McAvoy and Keira Knightley) has given some currency to the word. It is the story of a young girl, Bryony Tallis, who falsely accuses her sister’s boyfriend of rape, sending him to jail and then to war. His life is ruined. The book is the story of Bryony’s guilt: her desperate seeking to somehow atone for what she has done.

Instead of living in her wealthy parent’s estate in the safety of the country, Bryony trains as a nurse, working in the most dangerous part of London during the blitz in World War II. She wants to do anything she can to make up for her terrible deception. Reading the book or watching the film, one senses the deep need we all have for forgiveness and reconciliation.

The Christian faith proclaims that each of the breakages in our lives and relationships are symptoms of a much deeper rupture, a wound that lies at the very heart of creation. John Henry Newman put it: “We live in a world that is out of joint with the purposes of its creator.” Though not a Christian, McEwan expressed it: “You cannot ignore it when something deep has gone wrong. Something needs to be done to make it right. Atonement needs to be made.”

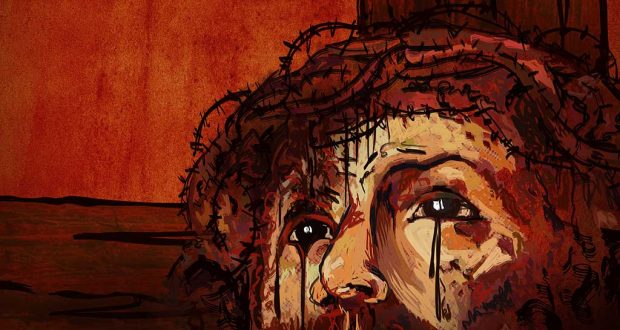

This is, of course, the very thing we celebrate at Easter.

In the Easter event, atonement was made. “God presented Christ as a sacrifice of atonement, through the shedding of his blood—to be received by faith.” (Romans 3:25)

God stepped forward in Christ to be “delivered over to death for our sins and raised to life for our justification.” (Romans 4:25)

Creation’s rupture was “covered over” (the literal meaning of the word “atonement”) with the Creator’s love and justice. Though the exact mechanism of this transaction might elude us (Wesley’s words are helpful: “ ‘Tis mystery all, the Immortal dies, who can explore this strange design?”) the result is an invitation to be ushered into the fullness of life Jesus offered in John 10:10.

Easter is not so much about the darkness of sin as the wonder of forgiveness, restoration, liberation and new beginnings.

But, as Lord Byron once said, “The beginning of atonement is the sense of its necessity”. Or to pinch a line from Don Francisco’s Christmas Song, “The rudeness of the setting ignites the jewel’s fire”.

As we take the time on Easter Sunday to celebrate Jesus’ victory over sin and death, let’s also enter fully into the Maundy Thursday and Good Friday traditions of quietly and deliberately searching our own hearts, naming rather than excusing our sin and self-interest, that we might experience the truth proclaimed in Hebrews 9:14, “How much more, then, will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself unblemished to God, cleanse our consciences from acts that lead to death, so that we may serve the living God!”

Simon Gomersall

Simon Gomersall is a lecturer at Trinity College Queensland.

Trinity.qld.edu.au

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline