While Christmas is associated with family, festivities and the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ, Trinity College Queensland’s New Testament lecturer Dr John Frederick explores how we can also use the Christmas story of Jesus’ birth to reflect on the “apocalyptic” in the traditional sense of the word—the revelation of that which was previously hidden—and how that may shape our thinking for the years ahead.

For most of us, there is a warmth, a magic, a timeless peace that comes with the Christmas season. Our childhood memories of Christmases past evoke in us a sense of transcendent wonder. Enjoying a good meal with loved ones, pausing to admire nativity scenes and colourful Christmas lights, and singing heartily along with the festive music that comes about only once per year.

These things help us return to a feeling of abiding hope, holy innocence, and supernatural rest. Many of us find that we deeply resonate with the classic Christmas song “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”. And, we long—as the song lyrics say— for our “troubles to be miles away,” even if only for a few days. We want to lose ourselves in the season . . . and hopefully to find ourselves sometime soon after the New Year.

No doubt, there is something worth keeping—even worth cherishing—in the peacefulness and restfulness that Christmas brings. The nostalgia and fond remembrance that it evokes in us is something I’d never want myself or anyone else to be without. Yet, when I look at the Scriptures, I start to wonder if in our eagerness to embrace the restfulness of the season we might have lost a sense of the restlessness toward which the birth of Christ is meant to call us. As noted theologian Jürgen Moltmann has said, “Faith, whenever it develops into hope, causes not rest but unrest, not patience but impatience. It does not calm the unquiet heart, but is itself this unquiet heart . . . Those who hope in Christ can no longer put up with reality as it is, but begin to suffer under it, to contradict it.”

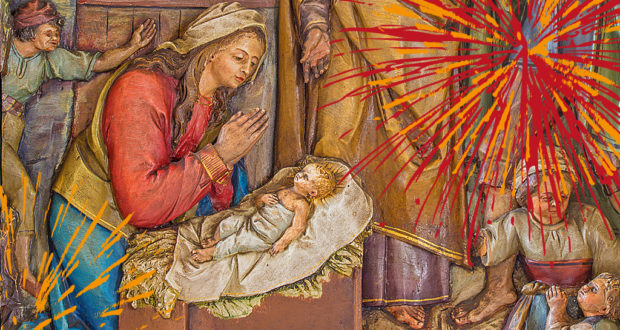

What if the birth of Jesus evoked in us, not merely the seasonal warm fuzzies for the status quo of religious affection, but a revolutionary zeal to see the victory of God in Christ change everything? What if the incarnation of God in a manger in Bethlehem was not a merely merry occasion, but one that would have been terrifying to Mary, Joseph, and the shepherds? What if it was an event that could be described—not as holly and jolly—but as vulnerable, dangerous, shocking, and dare I say apocalyptic?

In fact, this word—“apocalyptic”—is one that is applied to Jesus at many points in the New Testament. We tend to think of the word in negative terms, referring perhaps to the end of the space-time universe due to its association with the New Testament book of Revelation. However—contrary to the Christian movie industry—such a negative understanding of the word “apocalyptic” must be, if you will, left behind. The word in Greek apokalupsis refers to the revelation of that which was previously hidden.

In Galatians 1:12–14, St Paul explains that the Gospel he received was not delivered to him through human beings. Rather, it came to him through “an apocalypse (meaning, ‘revelation’) of Jesus Christ.” Far from being the natural outworking of the status quo, or something Paul expected—the apocalypse, the revelation, of what God was up to in Jesus Christ literally knocked him off his horse. It shattered his world, it woke him up. He was spiritually illuminated whilst physically blinded.

If we asked Paul whether he enjoyed the song “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” I think he would be perplexed. He would likely suggest that we change the title to “Have Yourself an Apocalyptic Christmas!”

Paul would not have viewed the birth of Jesus as a merry little happening, complete with eggnog, Sinatra songs, and celebratory seasonal cigars. Rather, he would have perceived Christ’s birth to be an apocalyptic intrusion, a disruptive event that smashed to pieces the expectations and worldly restfulness of the status quo, replacing it with the inbreaking of God Almighty in the incarnation of his son for the redemption of the cosmos. And, of course, Paul would add, an apocalyptic Christmas should be ever calling us to remember the gravity of the gospel and cost of the victory of God, namely that the events of the first Christmas led to Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, not to the return queue in Kmart. It is to the severe detriment of the true nature of Christmas that we let religious customs (even good customs!) or rank commercialism replace the apocalyptic power of the incarnation of God.

In fact, Jesus’ own name, which is mentioned in the birth account in Luke 2:15–21 often read on Christmas Day, is a Greek transliteration of a Hebrew word meaning “victory, deliverance, or salvation”. Thus, the manger wasn’t just an adorable, cute event; it was itself the initiation of the divine victory over the powers of sin and death through victory incarnate, Jesus.

When the Old Testament refers to the “victory” and “deliverance” of God (e.g. Psalms 96 and 98; and Isaiah 52:7–10); it uses the same Hebrew root as the word that is translated “Jesus.” Therefore, Jesus (“victory”) provides both the New Covenant lens and the literal fulfilment of the victory of God through Israel for the sake of the world. The victory of God in Jesus, beginning in Christmas, is thus the paradoxical joke of the gospel. Consider this: the greatest kingdoms and nations, the fiercest warlords and leaders, and the most brilliant thinkers and politicians have all been outsmarted and defeated by an infant in a manger in Bethlehem.

There is nothing less intimidating than a baby. And yet, a baby named “Victory” was God’s preemptive move in the metaphorical battle by which he is reconciling all things to himself. The vulnerability of the manger eventually led to the violence of the cross; violence inflicted on Jesus—not by God—but by “powerful” human beings intending to thwart the mission of Jesus.

Yet, profoundly, Scripture and the Great Tradition testify that through both his humble birth in the manger and his humiliating death on the cross, Jesus demonstrated that “power” and the “will to power” have been reframed by the paradox of the gospel. Vulnerability and sacrifice—not coercion, force, or violence—have now become the way of the people who follow the crucified God. All of this began on Christmas; and it changes everything. Or does it?

We must ask ourselves this Christmas season: is the humility of the manger and the humiliation of the cross the guiding paradigm and inspiration for our life together as the church, the body of Christ? Do we live by the apocalyptic message of peace, or do we think that—after all—the way to get things done in the church and in the world is through coercion, force, and manipulation? Do we behave more like the ones in “power” who crucified God, or do we adopt the ethos and character of the crucified God? Do we follow the way of the vulnerable God in a manger, or do we forsake that path for ecclesial pragmatism, politics, and worldly power—for the things that “work” and “get the job done”?

Have our Christmases been merry and bright; but not apocalyptic? Have we capitulated to the cultural Christ of comfort and commercialism, or are we seeking to see those things crucified in our flesh so that our lost, dying, and hurting world can receive more than a candy cane and a Christmas card this season but instead encounter the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ through us, through our ministries and through our churches?

An apocalyptic Christmas invites us to rest in the peace of the silent night in order that we can be preemptive peacemakers, holy troublemakers, and reconciled reconcilers in the light of day. The peace of the silent night is meant to shake things up; not simply to shut us up or settle us down. The restfulness of the silent night is not meant to serenade us into a permanent state of spiritual sleepiness in which the narcotic of religious nostalgia stuns us and subdues us, causing us to become complacent supporters of the status quo, at rest with the world in all its brokenness, injustice, and suffering.

The restfulness of the silent night is meant to be a missional rest, a Sabbath for the soul that energises and compels us to be restlessly active participants of the mission of God in the redemption of the world in and through Christ. My hope and prayer is that as individuals, families, churches and communities our Christmas may be flooded with the peace of Jesus Christ that brings both joy and apocalypse to the world.

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline