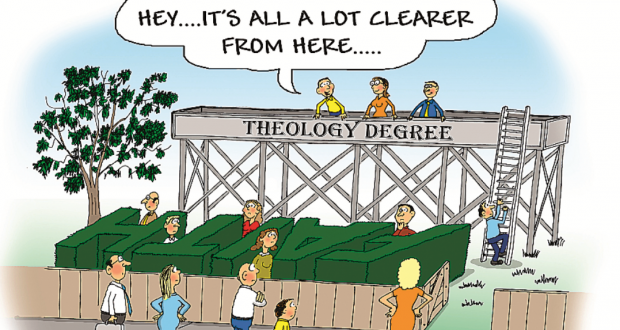

There were plenty of passionate discussions around how the Uniting Church forms people in their faith at the 31st Synod in October last year. Mardi Lumsden explores how theological study deepens and even shakes your faith, and why that could be essential to your faith journey.

The Uniting Church’s foundational document the Basis of Union outlines the importance of the education of church members and respect of scholarly pursuits. Paragraph 11 states: “The Uniting Church enters into the inheritance of literary, historical and scientific enquiry which has characterised recent centuries, and gives thanks for the knowledge of God’s ways with humanity which are open to an informed faith.”

Many Uniting Church members are working towards this informed faith though study and training, but what happens when new knowledge challenges core beliefs?

Trinity College Queensland principal and lecturer in practical theology Dr Aaron Ghiloni says studying any religion’s texts, practices and ideas is inherently demanding due to the complex and contested nature

of religious tradition.

“Moving beyond black-and-white essentialism towards the nuances of history and context requires patience

and subtlety.

“Although theological study is challenging it is a beneficial sort of challenge,” he says. “This challenge

of Christian learning goes to the nature of Christian faith itself: because faith is dynamic and living it must be engaged and reengaged throughout life’s stages.

“If such exploration is easy or tranquil, we may be doing it wrong.”

You gotta have faith

For Adelaide PhD student Caryn Rogers a growing passion for theological study took her on a faith journey she never expected. Growing up in the Pentecostal tradition Caryn had a very particular understanding of God.

“It was a very big God, very ‘angels and demons’ theology … I was speaking in tongues when I was six,” she says.

Caryn signed up for a Bible college course when she was 18 because she felt she was lacking biblical knowledge.

“It was really challenging for me because I had been brought up in a very conservative experience of church. I believed in quite a lot of out-there things and I believed a lot about the nature of God and the nature of the Devil and the presence of both of them in my life.

“I really hit rock bottom around mid-year because I had stripped away a lot of the faith stuff that I had known. I was studying the Old Testament and fascinated by that and studying doctrine so my brain was really coming alive and asking questions. I was finding that the feelings I had as a young child churchgoer―which were the power, warmth and hugeness of community―weren’t there anymore. I was engaging my brain and I felt like I wanted church to be matching that … When it wasn’t, I was really disappointed.”

While the faith of her childhood was inherently challenged, Caryn revelled in the intellectual side of Christian belief. The faith that made her heart sing as a child meant she longed to maintain her relationship with God while exploring the intellectual side of Christian texts and doctrine.

“I think I always really wanted to believe it because my new cognitive understanding never superseded the experiences that I have had personally with God,” she says.

Caryn continues to try to encounter God in a way that makes her brain alive as well as her heart.

“I think 17-year-old Caryn would say I have lost my faith and I have lost my way, but something is still there, a conversation that is not finished. I have friends who became atheists during their theology degree because there were too many questions unanswered. They wanted more absolutes and rationality to their beliefs; what they found was that the more they sought absolutes, the more they lost any faith they once had. I never got to that point.

“I think there is so much that we can enter into our dialogue with God that it is not so much about losing our faith as it is continually to increase it.”

Caryn continues to work on her PhD thesis on rhetorical structures of persuasion in the Hebrew Bible through the University of Adelaide.

Losing my religion

Former South African Presbyterian youth leader Gareth Beyers now aligns himself more closely with the Quakers than the faith of his upbringing.

“I didn’t know where I would end up but I wanted to be honest about the questions and trust that I would end up where I needed to,” he says of his theological studies at a state university.

“I’d asked some pretty fundamental questions around whether or not homosexuality is right or wrong, is there a hell and a heaven and are people from other religions going to hell.

“The other journey I was going on was a more spiritual journey looking at some of the early mystic writers. As I went further down that spiritual journey I found myself becoming more open but others [were] restricting my theology,” he says.

He says a big trigger for his change in beliefs was reading original biblical texts in Greek and Hebrew and finding a lack of clear-cut answers.

“To be able to view the Bible as a man-made, human-made book with people honestly grappling with this idea of a god and what God is, and they get it wrong sometimes and they get it right sometimes and the God character in the Bible changes as well. To find that out was pretty eye opening.

“In some ways church leaders have the luxury of being able to be professional theology thinkers. It is hard work; it is their job to spend the week reading the text, doing the hermeneutics to understand it and try to work out what the message is for us today, which is why I think people going to the seminary and losing their faith, or at least it changing a lot, is very common. I think there are a lot of ministers who don’t really believe some of the easy answers they give.”

Tell it to my heart

Aaron Ghiloni says an added challenge comes when we approach a religious tradition from the perspective of faith.

“Biblical study enables us to not only see that texts ought to be read in light of their context, but also that particular text demands to be taken seriously as scripts for the readers’ lives. The study of scripture and doctrine within a faith community makes demands not only of our brains but also of our souls and bodies.

“It is tough for some students to feel they have permission to engage with doctrine and scripture critically and curiously. Occasionally this reluctance is inadvertently fostered by the church when it promotes faithfulness, discipleship, orthodoxy, and consensus. If these values are taken as a demand for docility rather than an invitation to adventure than something of the protestant tradition has been lost.”

To explore your faith through courses at Trinity College Queensland visit trinity.qld.edu.au

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline

In response to your article in February 2015’s Journey Magazine titled “Shake, rattle and roll. How theological study can change your faith”, I was heartbroken to read that people attending theological college would lose their faith and become atheists. If that’s what’s going to happen to you, don’t go, especially young people who are easily impressionable to academic teachings.

A person’s faith and trust in God is so precious to Him. He does not want to see it ruined and them not even believing that He exists any more.

The Bible is a deeply spiritual book and like our minister says “It’s not like academic texts”. And like Paul says in 1 Cor. 1: 21a (NLT): ‘Since God in his wisdom saw to it that the world would never know him through human wisdom’.

Just read the Bible for what it is and it will bring you closer to God.

From

Miriam Bakker

Southport Uniting Church.

I can appreciate what Caryn has to say above. Going through Theological College was a very academic exercise (which it is meant to be). In the end I think the relationship with God (experience) and theological training (hopefully understanding) go together beautifully. Theology without the relationship is dry and lifeless. The relationship without the understanding makes you prone to being blown by every wind that come along. They are good together.