I had my third visit to Cape York in April for the funeral of Rev Silas Wombly of Aurukun. Silas was a clan leader and a Uniting Church minister.

Being raised at the mission, he worked as a stockman in the Gulf country before heading back to work for Comalco. He left for Nungalinya College in Darwin, and returned as the minister for Aurukun; the town population is almost universally Uniting Church in affiliation.

It was encouraging to hear that the workforce of Rio Tinto, which runs the bauxite mines at Weipa, is now one-third Indigenous—a significant achievement. It’s also remarkable for those of us who’ve been around a few years; we remember from the 1960s, the church and the Indigenous population being caught in a battle with the government and the mining companies to ensure that if mines were being developed, authentic engagement and consultation would be sought with local communities.

This tradition of being against commercial development goes back to the establishment of the Western Cape missions in the late 1800s. Then it was pearlers and beche-de-mer harvesters who were seeking to exploit Indigenous people. There’s a great read on this part of Australia’s history in John Harrison’s Mapoon under the Moravians 1891-1919, available for free download from smashwords.com

In the 1960s and 1970s the government and the mines were on one side, and the Aboriginal peoples and the church were on the other. It was a win-lose, zero-sum game. Neither side saw any benefit in engaging constructively with the other.

This attitude meant that the original Mapoon mission was demolished by the government in the dead of night, and the inhabitants sent to “New Mapoon”. Mapoon was gradually re-populated in the 1980s and 1990s. It is at Mapoon that we are seeking to build a new church to replace the one destroyed by the government in the 1960s.

Now we are seeing mining welcomed by the Indigenous community on the Cape as the harbinger of opportunity for employment and development.

But this didn’t come about naturally. The legal fraternity and people like Eddie Mabo played their part. It was the Mabo and Wik decisions that forced government to acknowledge that English common law recognised that a form of native title had not been extinguished. This in turn meant that mining companies had to deal with the Indigenous people of the Cape as people with a recognised interest in the land.

How that interest is recognised is still being worked out but this pioneering work by the courts has led to very productive outcomes.

It’s a sad indictment that governments—called to govern for the interests of all—had to have the courts force them to exercise justice.

As new mines develop and opportunities increase for the Indigenous population, the question of how they manage the integration of their culture with these new developments presents a challenge of a different order.

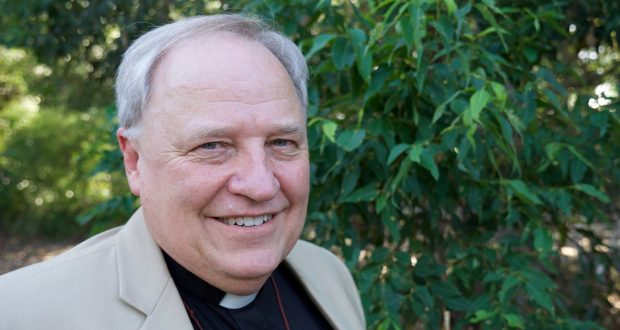

Rev David Baker

Moderator, Queensland Synod

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline