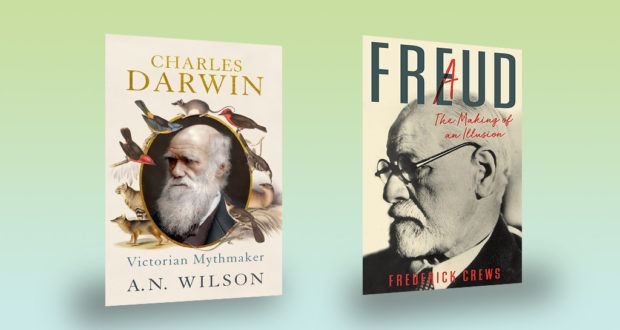

Freud and Darwin—two iconic-yet-controversial historical figures whose work continues to have a tremendous influence in helping us understand who we are and how we evolved. But with the release of new biographies on the pair, what other aspects of their life can we uncover? Nick Mattiske reviews.

The grand theories of Darwin and Freud, along with that of Karl Marx, are often said to have replaced older, traditional explanations from Christianity (and other religions) of why we are what we are.

None were believers. Darwin was the closest, subscribing to the establishment Christianity of his day before the death of his daughter and the implications of his science undermined what faith he had held. Freud and Marx were hostile, yet aspects of all three theories can be reconciled with Christianity—to a certain extent and depending on whom you ask.

With the end of the Cold War, Marx’s conclusions seemed to have been disproven or at least indefinitely postponed, and now two new biographies argue that Darwin and Freud also deserve toppling off their pedestals.

Both were snobbish, ambitious hypochondriacs who were happy to clamber over colleagues to claim credit for ideas that were being advanced by others. Both inspired followers to apply their theories far too widely, to the point of caricature. And, their biographers argue, the movements they supposedly founded have since moved on so far as to bear little relation to their original formulation.

A.N. Wilson doesn’t discount natural selection but argues that Darwin never really explained how it works. Wilson is insightful about how Darwin was a product of his (Victorian) times, though his grasp of the science is inadequate. And Wilson sometimes confuses Darwin with Darwinism. His book is iconoclastic, targeting an idealisation of Darwin, for which Darwin can’t always be blamed.

Crews’ relentlessly negative but engrossing biography of Freud has been criticised as a character assassination, but there is much to dislike in Freud’s character. In Crews’ account, Freud was a charlatan. He had little regard for his patients’ welfare, yet drew out their therapies in order to make more money. He made friends in order to benefit from their support before stealing their ideas and turning on them.

He switched theories to explain his patients’ troubles, made up case histories and used dubious methods and medications. An atheist, he was never-the-less susceptible to numerology and the paranormal. His dream interpretation theories were so vague as to render any extrapolation plausible, and he made the circular argument that his patients’ refusal to accept his wild diagnoses simply proved they were in denial.

When it comes to religion, while Darwin’s theory of natural selection did away with the idea of special creation, thereby making it easier to subscribe to atheism, only the most superficial reading would see it as tolling God’s funeral. After-all, it deals with the origin of species, not the origin of the universe.

In Freud’s case, while his identification of darker, subconscious forces mirrors Christian notions of original sin, his portrayal of religion as wish-fulfilment and the result of problems with one’s father ultimately says more about Freud’s own issues than that of humanity in general.

Nick Mattiske

Nick Mattiske is a bookseller and blogs at Coburg Review of Books.

Charles Darwin Victorian Mythmaker

Author: A.N. Wilson

Publisher: John Murray

2017

To purchase visit Hachette Australia

Freud: The Making of an Illusion

Author: Frederick Crews

Publisher: Metropolitan Books

2017

To purchase visit Allen and Unwin

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline