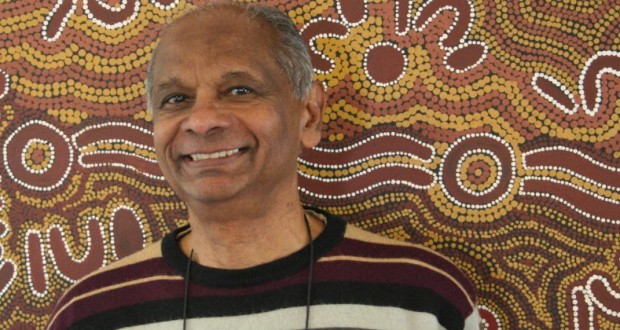

Servant leadership rooted in love for the other can make a radical difference. Rohan Salmond spoke to Mudgeeraba Uniting Church member Dr Dayalan Devanesen AM about loving action, bicultural healthcare and community empowerment.

Dr Dayalan Devanesen AM began his medical career with a blessing.

“When I was 12 I happened to meet Dr Ida Scudder, who founded Christian Medical College, Vellore,” he recalls. “She was 80-odd years old, and passed away the following year … she was bedridden by that time.

“When she saw [my brother and me] she called us over and said, ‘Son, what would you like to be when you grow up?’ I said, ‘I want to be a doctor’, so she made me kneel down and she put her hands on my head and said, ‘Son, be a good doctor’.”

Throughout his career as a doctor and public servant Dayalan, who is known as “DD”, has had a profound impact on the field of community health in Australia, particularly for healthcare in Aboriginal communities. Between 1973 and 2003 he worked in the Northern Territory, first as a Flying Doctor and later as Director of Indigenous Health in the Northern Territory.

The road to Alice

Five years after his blessing from Aunt Ida, DD was accepted as a student at Christian Medical College, where he developed his passion for a community approach to healthcare.

“That medical school on the one hand did rural work because that is what Aunt Ida, the founder, wanted. But on the other hand it is a trailblazer for modern science. It did the first renal transplant in Asia, things like that.

“Many of the students get carried away by the glamour of more modern medicine but I was always attracted by the community health side of things. I wrote a paper as a student saying God calls us out of the hospital to join him on the dusty, sweaty roads of India to serve the people where they live. This has been my theme throughout: delivering health care but working outside hospitals and institutional walls,” sasy DD.

After graduating, DD moved to Nagari to work in a remote mission hospital operated by the Church of South India. It served a population of 100 000 poverty-stricken people with a team of just a handful of doctors. The workload and emotional toll proved to be too much.

“After six months I had a nervous breakdown. I had an ulcer and was vomiting—very sick—but I was working night and day. Six or seven women would come to the hospital every night because they were having complications delivering their babies. It was very hard work. Children would die every day of preventable diseases like malnutrition, diarrhoea and tetanus.”

DD’s father came to visit after delivering the 1972 Cato lecture at the Methodist General Conference in Australia and suggested it was time for a break.

“He said, ‘Son you can’t solve the problems of India all on your own. Why don’t you take a break and think about life? I’m going to try and get you to Australia. Go for a year and do the public health course at Sydney University.’”

Six months into his course, a lecture on Aboriginal health left the usually jovial DD extremely disturbed.

“Infant mortality, 200 per 1000 live births; high rates of tuberculosis; leprosy; malnutrition; diarrhoeal diseases; pneumonia—these were so shocking to me.

“I thought, my gosh! This is what I tried to leave behind! That night I couldn’t sleep, and I knew my life had changed because I was running away, obviously. The prayer I had that night was, ‘Here am I, please send somebody else!’

“When I came down in the morning and looked in the newspaper there was a half-page ad desperately seeking doctors to work in Aboriginal health in the Northern Territory, so that was it. I put my hand up, completed the course and ended up in Alice Springs.”

Power to the people

The passion DD brings to his work is obvious; he is never afraid to learn and try something new. When he worked in the Northern Territory he brought a whole new collaborative approach to healthcare in central Australia.

“There was an initial advantage to coming from outside of Australia to work with Aboriginal people, but it was really all about attitude,” says DD. “It was partly my great desire to learn from Aboriginal people, you know? I wanted to be a learner as well as a teacher, and being a learner had huge advantages.” DD is almost giddy with excitement as he tells stories about his former patients and the things he learned from them: bush tucker, bush medicine and traditional art and storytelling.

Healthcare professionals in central Australia had previously written off traditional healers as witch doctors, but DD saw something valuable in the holistic, spiritual approach they brought to health. Together they introduced “two-way medicine” which combines traditional and western health care strategies and traditional healers were eventually employed by the Department of Health. This led to development and training of Aboriginal health workers by the Northern Territory government, the first program of its type in the world to register Aboriginal health workers alongside doctors and nurses.

“The solution at the end of the day is not the white solution. In fact the present solution has become the problem. It’s the Aboriginal solution that we’re looking for,” he says, “Unless you can allow Aboriginal people to assert themselves to be empowered to do things their way—even if they make mistakes it doesn’t matter, they’ll learn from it—we won’t ever find a working solution to the problems facing Aboriginal people.

“My approach has always been to follow servant leadership; you serve the people even if you are a leader … This is basically out of my Christian upbringing, wanting to serve rather than wanting to just go in and do marvellous things. Serving means getting to know who the other person is and getting to appreciate what it is they want to do.

“Look, people are the solution, not the problem, and the people have the answer to their problem. Our job is to listen to them, it’s not to go out and say, ‘Do this, do this, do this!’ but to ask, ‘What is it you usually do, and can we support that?’”

Empowerment is key

Now 68 years old and retired, DD is Vice-president of Roofs for the Roofless, an Indian nongovernment organisation founded and operated by his 99-year-old mother in Chennai.

“So I’ve gone full circle—I’ve left India and at the end of 30 years working in Aboriginal health I’ve retired and I’m working as far away as possible, back in India,” says DD.

Roofs for the Roofless has a community approach just as comprehensive as DD’s work in central Australia. Programs include a day care centre for children whose parents work in the fields, a respite centre for the elderly, a centre for women’s empowerment and a vocational skills college for young people who failed high school.

“Empowerment is the absolute key word. There are no handouts as such. It’s called Roofs for the Roofless because we started by building houses, but it’s not a handout—they had to make the bricks!—but it was a solid house.”

DD now spends several months in Chennai each year because, “How can I fully retire when my mother is 99 and is still working?” After 30 years of operation, Roofs for the Roofless is on the cusp of financial self-sustainability.

“Roofs for the Roofless doesn’t go out preaching the gospel, but we live the gospel through what we do. The people know we are Christians because of our loving and compassionate action.”

JourneyOnline

JourneyOnline